When we think of basic human needs, hierarchies often come to mind. What is it that people need and how are those needs related to human behavior? That’s the question that human services professionals often ask, and the one de-escalation trainers need to answer. Years ago, I learned through several personal and professional experiences that people act-out for reasons, not because of diagnoses. It does not matter if their reasons are real or imagined because regardless, they are real to the person in crisis. As responders, we need to address basic human needs at the point of impact; otherwise, any attempt at de-escalation is going to fail. That is why untrained responders usually end up being escalators rather than de-escalators.

We know that air, water, food, and shelter are basic human needs. Psychological theorist Abraham Maslow referred to these as physiological needs. They are the basic needs of the body to sustain life. Interestingly, he categorized safety as a separate level of need. On the surface, safety would mean security of life and limb. Until recently, I never completely understood just how much the feeling of safety is a basic human need just like food or water.

At Vistelar, we believe that human service professionals cannot function effectively if they don’t understand what drives human behavior. That doesn’t mean we need to be psychiatrists to work effectively. In fact, I have spent many hours teaching this same concept to psychiatrists who were interested in mastering the art of de-escalation.

Applying Our Training to Real World Situations

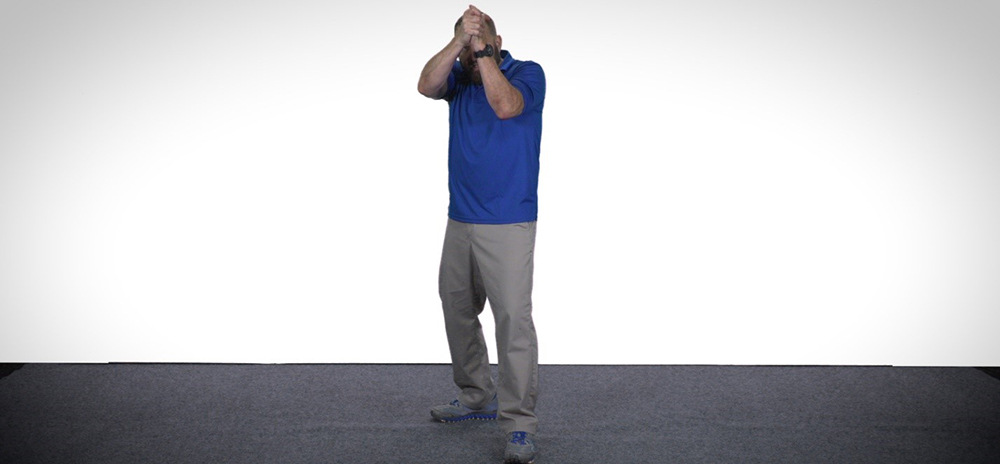

Once, while visiting a locked high-security psychiatric facility, I observed two security officers while they stabilized an actively suicidal patient. These officers were trained in the methods Vistelar teaches. The patient was reporting that he heard voices that were telling him to kill himself. The officers were safely and effectively stabilizing the patient in a chair. One of the officers was communicating with the patient, while the other remained silent: this is the one voice technique.

Despite the officer performing the verbal de-escalation, the patient was still in a state of hyper-vigilance and extremely frightened. At that point, the patient saw me and started looking me up and down to assess me for safety. Likely, he was assessing for two things: Was I real and was I a threat? I made eye contact with the communicating officer and nodded, signaling that I was going to take over communication.

I then said in a soft and confident tone, “Hi, Mr. Johnson. My name is Joel. I work here. You’re in a hospital. You’re safe with me and these officers who are holding you. Nothing can harm you here.”

I used his name when addressing him with a Universal Greeting, so he knew I was talking directly to him, and not one of the disembodied voices he might be hearing. Using someone’s name frequently is a method of adapting communication.

The patient then asked, “They can’t get at me here?”

“No, they can’t,” I replied. “We will protect you. You can stay here with us as long as you need.”

The patient exhaled in a long sigh and visibly started to relax. I then signaled the officer to resume communication and I stepped back out of the intervention to observe.

The officer then asked, “Can you feel my grip on your arm? That’s me, Tom. I’m real. You’re safe now. It doesn’t matter what the voices are saying.”

“You’re real?”

“Yes, I’m real. So is my partner on your other arm. You see us? We won’t let anything happen to you.”

Within a couple of minutes, the patient was regulated, and the manual restraint was terminated. Then, he asked for something to eat and cooperated with the intake nursing staff while waiting for his snack. I understood then that as long as he had felt threatened, he just wouldn’t have regulated. No amount of food, water, or promises of a warm bed would have de-escalated his crisis until he understood that he was safe.

Early on in my public safety career, I worked at an urban medical center, with a busy emergency department that catered to the medically underserved. Typically, our patients ranged from children with minor injuries and ailments and homeless adults suffering from exposure and frostbite to people in psychiatric crisis, typical heart attack and accident victims, and the casualties of gangland shootings. The E.D. was always full, and the neighborhood was never safe to walk in at night.

My favorite place to work was the emergency department. I always volunteered to take that “rough duty” during roll call briefings, much to the relief of some of my fellow public safety officers. After a year of nearly nightly service there, I became an integral member of the emergency medical team, and the E.D. director even sponsored me to attend EMT school.

Ultimately, I started to think of it as my E.D. I was young, eager, and had faith in my excellent training (incidentally led by one of Vistelar’s founders, Gary Klugiewicz). I also had faith in my weapons, equipment, and body armor, which foolishly made me feel invincible. In those early days besides Gary Klugiewicz, I also had a few other significant role models, who taught me how to keep people safe in ways that went beyond my primary training.

At the medical center, we sometimes did joint foot patrols with district police officers whose patrol areas included the medical campus. On one such night, while I was on foot patrol with a city police officer, we were standing in front of a dead-end alley comparing some notes when a woman ran toward us out of the dark frantically screaming for help.

Though we were both visible under the streetlights and in full uniform, she ran right by us and into the back wall of the alley, where she collapsed and continued to scream. “He grabbed me!” she screamed at the top of her lungs, “He tried to rape me!”

While I radioed in the contact and kept watch at the end of the alley, the police officer started to walk toward the terrified young woman and raised his flashlight to get a look at her. When the light met her face she screamed in terror, and it was pushing her deeper into her state of panic. The officer then lowered the light to her waist and hands, assessing her for weapons and injuries, then down to her feet, before finally turning it off. There was still enough light flooding into the alley from the street, for them to see each other.

When he took a step forward the woman screamed and kicked her feet out towards him. The officer stopped and squatted down, reducing his profile.

“My name is Fernando. I’m a police officer,” he said softly and quietly. “You’re safe now.”

“Stay away! Don’t touch me!” she screamed.

The officer picked up his flashlight again and shined it on his shirt badge. “You’re safe with us.” He then shined it back towards where I stood by at the mouth of the alley. “He can’t hurt you now. We will protect you and take care of you.”

The woman finally stopped screaming and started to sob uncontrollably. Between deep sobs, she told the officer details about the man who tried to assault her. While she wailed, he spoke softly and intermittently, trying not to overload her limited ability to process. And when he spoke, he never made any of the classic mistakes that I had made a few times already in my early career.

He identified himself clearly, even though he was in uniform. He never told her to calm down. He never drilled her for details before she could process mentally. He never interrupted her. He spoke slowly and softly and told her that she was safe. He let her set the physical boundary (distance) and reduced his profile by squatting down to her level. By doing all these things, while not doing others, he made her feel safe even in that dark alley in the roughest part of town on the scariest night of her life.

While the woman finally started to compose herself, the officer looked back at me and said, “Joel, make sure our back-up and the medical team don’t come running into the alley. Tell the medics to enter slowly and warn me quietly when they get here.”

Just then, a city squad rolled up slowly to the curb without lights or sirens because Officer Fernando had radioed them to respond quietly. On that night he had thought of everything. Before long, the woman’s attacker was in custody, and she was being treated in my E.D. with her family at her side.