Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 5

Bystander Mobilization (Part Two)

“The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.”

– Albert Einstein

Bystander Intervention (Part Two)

Up to this point, we have already covered several keys to bystander mobilization, including:

- Noticing the event through situational awareness, determining baselines, and identifying pre-incident indicators and precipitating events.

- Interpreting the event as requiring help by addressing ambiguity and conformity, the diffusion of responsibility and the bystander effect, and evaluating the concern for safety versus the concern for life.

Now we will cover the next three steps to bystander mobilization:

3. Assuming personal responsibility to help.4. Knowing how to help.

5. Implementing the help.

Step Three: Assuming Personal Responsibility to Help

- Don’t rationalize away responsibility (diffusion of responsibility).

- Social norms affect whether people feel they should help.

- Explicit and implicit authority to help varies and impacts one’s prescribed duty to help.

As mentioned previously, the diffusion of responsibility greatly reduces helping behaviors. It is easy to assume someone else will do something, and it is easy to say, “it’s not my problem.” However, the need to end lateral violence isn’t about doing what is easy; it’s about doing what is right.

assume someone else will do something, and it is easy to say, “it’s not my problem.” However, the need to end lateral violence isn’t about doing what is easy; it’s about doing what is right.

The world needs more helpers. Have a bias towards action; do not assume that someone else will handle it. In fact, assume someone else won’t. Be the first, step up, and enlist others to help you. Verbalize your intentions to intervene, if safe and appropriate, and be specific, e.g., “I will make sure they are okay and call medical if needed; please go find the maintenance technician and a supervisor.”

Additionally, social norms will impact whether people feel like they should help or not.

Social norms are often referred to as “informal rules that govern behaviors in groups.” As I’m sure you’ve put together, social norms are inherent to the process of establishing a social contract. Social norms are central to the production of social order, as we all need to know what is expected of us and what the repercussions would be if we don’t adhere. With respect to assuming personal responsibility to help, it is important to understand the influence social norms have on the group; helping others with no expectation of anything in return is altruism. A strong pro-social norm among the group will lend to more altruistic behavior because your in group is more inclusive.

Finally, people are more likely to take action when they are in positions of explicit responsibility (such as managers and supervisors)because taking action (or enforcing the rules) is implicit in their job role and is expected by others. However, throughout this book, the point has been made to encourage taking action, even without prescribed authority.

“You must never be fearful about what you are doing when it is right.”

– Rosa Parks, American activist

Step Four: Knowing How and Choosing the Best Way to Help

- Determine what knowledge or skills are necessary to intervene and identify if you have those skills.

- People who are more knowledgeable about the situation can better evaluate alternative courses of

- Other factors that influence helping at this stage include perspective-taking and engagement recognizing obedience to authority or perceived authority.

Helping others and intervening is not just about one decision. Failure at any step will result in no help, so we must also understand how social context affects individual behavior and an individual’s decision to intervene.

Consider these barriers to helping:

- Individual variables such as personal knowledge or skills, confidence, and having a sense of social responsibility.

- Victim variables such as the appearance of the victim, friendship with the victim, perceived deservedness of the victim, and whether or not they will accept help.

- Situational variables such as the severity of the victim’s need, the number of other bystanders present, the perception of the cost of helping, environmental conditions, and whether there is strength in numbers/other helpers present.

Research indicates that people are much less helpful or heroic than they think. The situational factors of a situation (such as the bystander effect or perceiving the costs of intervention as being too high, i.e., “I don’t have time to help them right now. I have to go home and make dinner.”) go the furthest in determining the likelihood of intervention. The first thing you need to do is determine what knowledge and skills are necessary to intervene in a given situation. For something like a sexist or racist comment, you will need to have the ability to manage proxemics, appear concerned, create a supportive atmosphere, and sincerely deliver an engagement phrase to either the actor, the person victimized, or a supportive ally (all of these concepts will be covered in greater detail in the next chapter). If you have confidence in your ability to do all of those things, the likelihood of you helping in that

type of situation increases.

Additionally, having sound threat and risk assessment skills will help you determine the best course of action and alternative courses of action. By conducting a threat and risk assessment of the situation, you will be able to evaluate what resources you have available, such as other staff members, equipment, or time. You will be able to determine if you should intervene now or in a different way at a later time (this will be covered in more detail in Step 5).

Step Five: Implementing the Help

- People who have practiced the skills are more likely to intervene.

- People who are well trained are more likely to help safely and effectively.

Bystander intervention skills are life skills, and there is no doubt that they need to be practiced. There are multiple ways to practice using the skills discussed throughout the course of this book, and it is imperative that you train with “fire drills,” not just “fire talks,” whereas you physically practice the skills and work to apply them in context - incorporating critical thinking and decision making. The two examples below are examples of “fire drill” type training options.

One way is to brainstorm conflict scenarios (by yourself or with others) and then identify the red flag interjection (or intervention) points. Once you’ve identified the points for intervention, write down possible solutions and possible scripts. You may be surprised at how many solutions you can come up with, especially when working with others. Oftentimes, when I run live bystander intervention training workshops, I may see 20 different solutions from 20 different people for one specific scenario, and the group is usually stunned by the perspective and creativity of others.

Another way to practice your intervention skills is to run through live training with realistic training scenarios. This type of training should be conducted with a team of people who have a strong understanding of the material. By walking through live scenarios, you can practice not only identifying the interjection points but also the skills of managing space, communication alignment, the delivery of engagement phrases, and the use of redirection and persuasion. The more you practice, the more confidence you will have in the skills, and the more likely you will use them.

Quick Tips for Taking Appropriate Action

- If you notice an event out of the ordinary or observe a laterally violent behavior, trust your instincts and initial gut feeling.

- Ask yourself, “Could I play a role here or is someone else better suited to respond?”

- Assess your options to help.

- Evaluate the Look for low-risk options and decide to act now or later.

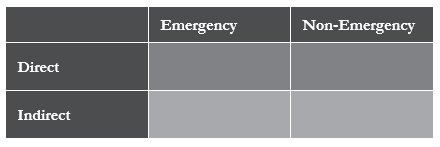

When talking about bystander intervention, people often think that in order to intervene, you have to perform some cape-toting superhero action. That could not be farther from the truth. Small interventions, either directly (in the moment and engaging with the person displaying the behavior) or indirectly (perhaps after the fact or by involving another or more appropriate staff member), will dramatically alter the course of the event.

Here is an example of using this simple quadrant in your decision- making process:

Imagine witnessing a coworker gossiping to another employee over their lunch break. You hear them make several inappropriate and inaccurate comments about a supervisor - specifically about how they handled a particular incident. You were involved in that incident and you know the gossipy comments to be untrue. At this moment, you have a couple of decisions to make. The first decision is whether to ignore the comments and walk away, or if you determine there’s a need, to address it.

Given everything you’ve read so far, we are going to assume that you’ve made the decision to address it. Now you can choose to intervene directly in the moment, by engaging in the conversation and tactfully correcting the false information with one or both parties. This action would qualify as a non-emergency, direct intervention.

However, you could make the determination that intervening in that particular moment would be ineffective. As you’ve read previously, there are numerous reasons why you may not choose to intervene in the moment, such as you don’t know exactly what to say or that you’re concerned you may offend the person and become the target of untrue gossip yourself. So then, you could choose to indirectly intervene by addressing the comments made after the fact - either with the person that made them, with the person that they said them to, both parties, or perhaps another employee who may be better equipped to have the conversation. These would all be examples and variations of non-emergency, indirect interventions.

As you can imagine, different situations require different responses. There’s an infinite number of ways we can work through them. Situations you encounter may not be as clear as the above example, but understanding and thinking through how situations play out will help you respond to situations in the future.

Case Study

“Dispelling the Myth: If you say something, it will make things worse.”

By Joel Lashley, Confidence in Conflict for Health Care Professionals: Creating an environment of care that is incompatible with violence, 2015, P.2

This myth is probably the most damaging. We’ve all heard this one. Worse yet, some of us have probably come to embrace it on some level. So, if you have heard this myth, forget it. And, if you hear someone say it, correct them.

The fact is, if we ask someone confidently and respectfully to stop behaving badly, they usually will comply. When we say nothing while people behave badly in our presence, the non- verbal messages of silence are permission and submission.

Specifically, if we say nothing when people threaten or even demean us, the non-verbal messages are, “It’s okay to behave that way” or “I have no authority to act.” Perhaps the worst of all nonverbal messages is, “I’m afraid.” Failing to speak up when people need limits set on bad behavior usually ensures we’ll get more bad behavior, and it will escalate.

If we focus on behavior, the attitude will follow. Skilled communicators focus on a person’s behavior, not their attitude, which is important in developing a therapeutic relationship. What we naturally do is focus on a person’s attitude, hoping their behavior will improve. This rarely works and can even backfire as the aggressor feels empowered by your attempts to assuage their anger by incessant apologies, allowing them to vent, and otherwise rewarding their bad behaviors. To make things worse, if all you have been trained to do is service recovery and/or crisis intervention, then appeasement is probably the only skill you have ever been taught.

Let’s take a look at how this plays out in the following story:

The man had arrived at the walk-in clinic three hours ago and had already asked twice how much longer he was going to have to wait to see a doctor. He left work at lunchtime to finally seek medical care because nothing he had tried over the past three days seemed to be helping his abdominal distress. He tried to get in to see his family doctor, but no appointments were available that day, only adding to his anxiety. His wife kept calling his cell every 30 minutes or so to check on him and remind him that their daughter had a soccer game that afternoon. Finally, he was beginning to boil over.

“So, what’s taking so long? Aren’t you at a walk-in clinic?” she said sarcastically. “I thought you were supposed to just walk-in and get treated right away. Isn’t that the point?”

“How should I know? They’re busy, I guess,” he replied. “What about Ashley’s game?” she asked.

“I’m sick! Do you really think I can go to that game tonight?!” he shot off angrily, feeling hurt by her indifference to his ailment.

“Well, I at least need you home to watch the other kids, so I can take her. It’s an important game!” she shouted back.

“I just told you I’m sick!” he shouted into the phone. “All of her f*****n games are important! Why don’t you just take the other kids with you?”

“I’m the assistant coach! How the hell am I supposed to watch them and coach at the same time?” she fired back.

“Oh, okay then. I’ll just leave and be right home!” he replied. “And thanks for the concern! I could have f***ing stomach cancer for all you know!”

The receptionist made every effort not to make eye contact with the angry man on the phone and just went busily about her job. Then a nurse stepped out from the back and handed her some forms to process, paying no more attention to all the shouting and cursing than if it had been the hum of an air conditioner. To her, it was just another familiar background noise of the workplace, like the beeping of an I.V. pump.

Finally, a lab tech stuck her head into the reception area and asked, “What’s going on?”

“He’s fighting with his wife,” whispered the receptionist. The lab tech scanned the room and saw an elderly couple stand up. With his wife close on his heels, the elderly man scooted quickly behind his walker, intent on creating as much space as possible between themselves and the angry man. Some patients crawled deeper into their well-worn magazines, while others looked on disapprovingly. Others struggled to distract their children’s attention from the angry man’s shouting and profane language.

“Shouldn’t somebody say something?” asked the lab tech. “Tell his nurse,” replied the receptionist.

The lab tech went back to the treatment area and quickly spotted the physician’s assistant and one of the nurses huddling together over a medical record. “Do you hear that guy yelling out there?” she asked with a puzzled expression. “I hear him,” said the physician’s assistant. “Did the receptionist say anything to him?”

“Doctor Jenkins should probably say something to him,” chimed in the nurse.

“He’s kind of busy right now for that,” replied the PA.

“In that case,” replied the nurse, “I’ll try and get one of these rooms cleared out as soon as possible so we can get that guy back here. He sounds like he’s just angry about the wait.”

“Good idea,” said the PA. “Hopefully that will shut him up.” Hurt and angry, due to his wife’s badgering and uncaring attitude, the angry man hung up on her mid-sentence. Then he stood and walked urgently up to the receptionist, yelling, “What the hell is taking so f***ing long?!”

For the first time, she looked up and made eye contact with the angry man, simply saying, “I’ll tell your nurse that you’re waiting.”

So, what do we do next? Just as in the example at the beginning of this chapter, the bystander effect hinders the decision of who is responsible for acting. Therefore, we must begin by making it clear that it is everyone’s responsibility to do something when an inappropriate behavior or potentially unsafe situation occurs, whether the actor is a fellow co-worker or a member of the public.

Then we have to give them the authority to act. In hospitals, when people act out, staff may feel even less able to intervene because of the mythology of healthcare violence discussed in Chapter Two. In training, we need to demonstrate how violence occurs and train staff to intervene as a team.

Bystanders generally know right from wrong but are unsure of how or when to take action to prevent a situation from getting worse. Most people think that intervention strategies require some drastic form of physical intervention; however, many appropriate strategies have very little to do with physical defense and have everything to do with communication skills.

All that aside, providers must understand when personal intervention isn’t the safest or best option and when to seek help. In the event of physical contact, personal defense options will be required. These skills can only be developed through dedicated instructor-led training.

Nothing can replace well-trained providers and security personnel when one is seeking to prevent and mitigate violence. But even a well-trained staff needs policies and procedures that work together to reduce and prevent violence. If we’re not all on the same page, we will continue to struggle with laterally violent behavior and its consequences and repercussions. The importance of communication and non-escalation/violence prevention skills, including bystander mobilization training, cannot be overestimated.

“For things to change. We must change. For things to get better, we must get better.”

– Heidi Wills, motivational speaker and civility thought leader

Key Takeaways

- Have a bias towards action; do not assume that someone else will handle it. In fact, assume no one else will.

- The situational factors of a situation (such as the bystander effect or perceiving the costs of intervention as being too high, i.e., “I don’t have time to help them right now. I have to go home and make dinner.”) go the furthest in determining the likelihood of intervention.

- Intervention options can be categorized as direct or indirect, emergency (life-threatening) or non-emergency (non-life- threatening), and will vary depending on your training, experience, and role within the organization.

- Small interventions, either directly (in the moment and engaging with the person displaying the behavior) or indirectly (perhaps after the fact or by involving another or more appropriate staff member), will dramatically alter the course of the event.

- Appropriate intervention strategies often have little to do with physical defense and everything to do with communication skills.