“Healthcare is a High-Stakes Profession” - Episode 2

Host: Al Oelschlaeger

Guest: Joel Lashley

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube.

One of the most essential but often overlooked skills in healthcare is the ability to de-escalate critical situations. Healthcare workers tragically often feel that dealing with combative people is simply part of the job. But what if they were trained to mitigate violence? Would their working life improve? Al sits down with Joel Lashley to discuss common problems healthcare workers face in everyday situations on the job. Oelschlaeger and Lashley both have extensive experience in the healthcare industry and know firsthand the very real and potentially violent situations healthcare workers face. Lashley wrote the book Confidence in Conflict for Healthcare and created the Point-of-Impact-Crisis-Interventions program at Vistelar. Using real examples from the healthcare workplace Lashley discusses how closing the gaps in training can empower healthcare workers to confidently keep themselves and patients safe.

To learn more about non-escalation, de-escalation, and personal protections visit vistelar.com

Allen Oelschlaeger: Welcome to another episode of the Confidence in Conflict podcast, your destination for learning how to better manage conflict in both your personal lives and your professional life.

Allen: So, I’m here today with Joel Lashley. Welcome, Joel.

Joel: Morning, Allen.

Allen: Yeah, it’s good to have you again. If you could just give everybody just a quick update on who you are and your background, and then we can get into it.

Violence in the Healthcare Industry

Joel: Okay. Well, as you know, Allen, I worked most of my professional life, last 25 years or more, in healthcare, mostly as a responder to conflict and violence, and complaints in other issues in hospitals.

Allen: Yep. Did you know we … I think one of your cooler things is you wrote a book about this back … What was that, about three years ago? I remember I [crosstalk 00:00:58]

Joel: Yeah, I wrote a book, Confidence in Conflict in healthcare, and the notion was that we could make clinical environments less compatible with conflict. That was the idea behind it.

Allen: As you know, it’s gotten quite a reaction by folks in healthcare. I remember you told me at the time, and I’ve probably heard it, I don’t know, probably 100 times since then, that healthcare’s one of the more violent professions. Maybe the most unsafe profession in the country.

Joel: Yeah. You know, for a non-fatal assault and, of course, there are fatal assaults on occasion, but where there’s aggressive consumers, that would be patients, and sometimes families and visitors. Assaults on nurses are higher than just about … and healthcare workers, in general … just about any other profession.

Joel: It’s not just an American problem. It’s true all around the world.

Allen: Yeah. It certainly gets the news a lot now. I don’t know if you … people that pay attention. It just seems to come up a bunch, about what’s going on in healthcare. I think there’s a higher level of aggression than there was even just a few years ago.

Allen: Joel, you’re the expert at it, so, what are we going to do today? I know you got a story to tell and a specific topic we want to cover.

Joel: Yeah. I want to talk about how, you know, the relationship, the position between the patient and provider can be a difficult one, and understanding that instead of denying it is something that’s important.

Joel: When most people went into healthcare, they probably didn’t think that, “Well, I’m going to, you know, deal with aggressive people more than if I’d gone into another profession.” They usually find out as an afterthought, which has always been kind of interesting to me. I think, maybe, now people are starting to realize that they’re making a career choice that’s going to involve a lot of physical and emotional, and, sometimes, challenging work, not just with, you know, what they need to know, and what they need to deliver, but how to deliver it in a way that keeps them safe and affects their patient outcomes.

Allen: Yeah. You know, we call these folks contact professionals, and there’s people in a lot of different industries that have that role, but it’s a tough role. You have to do your duty of your job in healthcare. It’s blood pressures and IVs, and whatever, but you also have to make sure the patient is feeling like you care, and there’s some empathy there, and they think you’re listening, and then you’ve got to worry about your personal safety, for all the reasons we just talked about.

Allen: Then what’s changed in the last few years, the camera’s always on. So, no matter what you’re doing, there’s probably somebody recording it.

Joel: Yeah. Somebody recording it and somebody judging it.

Allen: Yeah. Yeah. So, tell me the story. So, what’s … I know you …

Joel: I mentioned a story a few years back where I needed to do a mediation between a family and some providers. The issue was, you know, healthcare is a high stakes profession. You know, we’re not selling cars and fixing basements. You know, we’re working in people’s lives, in their futures. So, everyone that walks through the door has a set of problems, relationship problems, financial problems, health problems, all mixed in with, you know, their pain, their fear, their illness, their recovery.

Joel: On the other hand, the provider, you know, they’re … We may tend to discount their stress. You know, there’s a nursing shortage. There has been for a number of years. It’s difficult to find and retain good nurses, and other healthcare providers. So, that’s always a challenge, on top of the long hours, weekends and holidays, working nights, the stress at home that’s involved with their profession.

Joel: So, everyone in that environment is under stress, really.

Allen: Well, I think everybody’s had this experience, right? As you know, I had a little health issue a couple years ago, and spent some time dealing with the healthcare system. It’s real. Then, you know, we’ve all had family members that dealt with it. I know you had a little incident a while back.

Allen: So, it’s scary. Right? You’re in there with a lot of different things going on, and it’s easy for conflict to raise its head, and for things to get out of control.

Joel: Yeah. You know, I’ve been a consumer for longer than I’ve been, you know, working in the healthcare profession, and I’ve been in those high stakes situations, family members, children that had chronic health conditions, painful health conditions, long term health conditions, deaths in the family, my own health crises, probably more than most people have, by this point in my life.

Joel: So, you know, I’ve spent a lot of those long nights sleeping on a hospital bed, you know, floor, a hospital room floor. I’ve been that person in a critical care unit that when the nurse looked you in the eye, you knew they were saying, “Visiting hours don’t apply to you.” So, I know what it’s like [crosstalk 00:06:54] both ends of the schedule.

Allen: Yep, yep. As you describe yourself, right, you’re a little bit of a healthcare violence nerd, that’s a result of all that experience. But anyway, back to the story. So, what happened here, and what …

Joel: What I like about this story is it kind of solidified some of the things that I’d learned over the years. By this point, I already was a violence nerd. That’s why I was called into these kind of high stakes discussions.

Joel: This discussion was between a physician and his staff, concerning a man whose child was gravely ill. The father had been banned from visiting his own child in this hospital because he had been so aggressive, assaultive on staff. We understood that his child was gravely ill. I think it’s also important to remind ourselves that, particularly in that place where I was working at that time, it was a children’s hospital, was filled with gravely ill children. The vast majority of parents, and I’ve been that parent at the bedside of a gravely ill child, they don’t insult and disrespect, and more importantly, touch without permission and physically assault the provider staff. You know?

Joel: But this father did. After a cycle of trying to rein in behavior, when he became assaultive, he was banned from that particular hospital. So, the issue was the patient was getting sicker. Right? So, he was asking permission, and his wife was asking permission, to visit his child in the hospital again, and under what conditions that could be done. Of course, we wanted to do that. We wanted to make that happen.

Joel: So, I was going to meet with the parents, and a physician, and some of his staff members, and mediate them. We actually had a good outcome after that. It required a lot [crosstalk 00:08:58]

Allen: But Joel, just a little aside, but just a little … So, you can actually get banned from a hospital based on your behavior. That’s a little bit of a warning to everybody. [crosstalk 00:09:12]

Joel: That’s the thing, you know. Hospitals have traditionally been very accepting of violence, and [inaudible 00:09:16] this story’s going to be about. It’s just like in any other relationship, you know. You can call it a domestic violence relationship, is often a good parallel. The more disrespect and aggression you accept, it often leads to violence, and if you’re accepting of that violence, you’re stuck in a cycle of it.

Joel: Healthcare is really one of those kind of situations, one of those kinds of environments that if it’s practiced as it has been traditionally, it’s really very compatible with violence. This story kind of illustrates that a little bit.

Joel: So, I’ve heard this in hospitals, where there were difficult visitors and such in hospitals, is that at the end of life all bets are off. Right? So, they took those sorts … What they were saying was, “Yeah, we know this guy’s been a problem, but it’s the end of life, so, we’re just going to let him in and take our chances.”

Joel: Well, I was supervising this process. We didn’t do that. We had scheduled visits. We had emergency contacts for when things got worse. There was supervised visits. So, the hospital had to give a lot of resources, and time, and money to make sure these visits happened, but they were happy to do it, with the understanding that they were going to be safe.

Joel: You know, there are hospitals where they wouldn’t even consider banning a parent from visiting, or a husband, or a wife, from visiting their patient. But after some tragic incidents, that policy kind of changed. You can wind up on that short list. “Well, I’m sorry, but your husband’s welcome here, but you’re not.” You know, it’s unfortunate that we had to get to that point, and we like to work with families, but at some point, how much risk do we take, and do we expect our staff to take, before we take action?

Joel: That’s what we’re talking about. The old all bets are off paradigm had to go.

Allen: But Joel, your point here is that some hospitals still have that attitude [crosstalk 00:11:15]

Joel: They do [crosstalk 00:11:18] It’s unfortunate that it may take a tragic incident or a high nursing turnover. You know, when you look at nursing job satisfaction surveys, you find some interesting kind of data that comes out of them.

Joel: I’ve read somewhere, “I’m happy with my pay. I love my boss.” You know, “I like the work, but I just can’t tolerate, you know, the disrespect. I can’t tolerate the aggression. I’ve been assaulted too many times.” That kind of thing. There’s very few professions where you would get something like that. Sometimes in retail and other ones, where the stakes aren’t so high, where people just do move on. But these are people that have dedicated, you know, that undergraduate degree, specialized nursing training, sometimes postgraduate degrees, to finally reach that point of burnout. You know, “I can’t do this anymore.”

Joel: The thing they point to very often, if not most often, is involved with these sorts of issues. What I think we have to remind ourselves though is that most patients are disrespectful, they aren’t aggressive. Sometimes they melt down when they’re in crisis, and if we get good at dealing with that, that’s to be expected, and we can actually deal with that in a very therapeutic manner.

Joel: The old yelling, cursing, threatening, you’re not moving fast enough kind of mentality, you know, on one hand, we might blame the victim. You know, the nurses are, you know, some of the feedback I’ve seen analyzing some of these incidents is the nurses were snotty, or they were too slow, or these sorts of complaints. You know, these are value judgements. [crosstalk 00:13:26]

Allen: With the message that they actually deserve it, in some way.

Joel: Yeah. That’s usually the message in the eye of the aggressor, again, including in a domestic violence relationship, we tend to blame the victim.

Allen: Right. Yep.

Joel: Without digressing too much, in this particular meeting, while we were waiting for the parents to arrive, was just making some small talk with the physician and some of his staff and there was a nurse there who was an older nurse. It was a woman. Very highly educated. You know, had a master’s degree in nursing. Having a discussion with her about her career, which is very long and accomplished. She worked in several different fields, you know, surgery, cardiology, pediatric cardiology, things like this. She was a very well rounded, fiercely intelligent woman.

Joel: While we were talking, and she was capping her career for me, I asked her, I said, “Have you experienced much physical aggression on the job?” She said, “Well, no, not really. It’s not that big a deal.” So, I asked her, I said, “You ever been spit on?” She said, “Well, yeah. That’s happened.” So, I said, “You ever been shoved by a patient?” Goes, “Well, yeah, a couple times.” “You ever been slapped across the face?” She said, “Well, yeah, actually that has happened.” “You ever been kicked?” “Yes.” “Punched? Kicked? Hair pulled?” “Yes.” “Scratched?” “Yes.”

Joel: Well, what is she calling aggression?

Allen: Yep. She just expected that. That was just part of the job.

Joel: Part of the job. That part of the job mentality is part of the problem. Where do we draw the line, and more importantly, how do we draw it? What is it about the clinical environment that, maybe, you know … It has to be more. It’s certainly part of the problem because that’s step one. Everybody who shows up doesn’t want to be there. They walk through the door with several problems.

Joel: The staff are overworked. Right? They work in … often overworked. They work, you know, a very physically and emotionally demanding job. You know. It affect their family life. It affects their physical life, their psychiatric well being. All those things. Then we put them together and we watch to see what kind of results we have.

Joel: In no other profession, you know … There are other professions, police work, corrections, things like that, social work, where we have to train people how to work in these relationships, how to set the social contract. You know, everyone’s heard someone say this. “Well, they need to teach her how to talk to people.”

Allen: Yeah. [inaudible 00:16:31]

Joel: You know? That’s really what we’re looking at. We’re not telling people what to say. We’re helping them understand how to say it, and what things mean when they receive it, and how we can redirect it, how we can persuade people.

Joel: We’re in a profession where, you know, we’re not very good at persuading people to go with the program. That’s not only with treating us with dignity and respect, first by modeling that behavior, and then how to cooperate with therapy. You know, that’s a big problem, especially nowadays.

Allen: Well, I think you’re describing two ends of the spectrum, right? I mean, there’s the … it’s how to communicate with people so that … or talk to people such that they … this conflict, this aggression, doesn’t occur. There’s obviously things you can do to minimize things escalating, and I know that was a lot of what was in your book, but then once somebody … things do escalate and somebody’s being too aggressive, and they’re pinching, or shoving, or slapping, or whatever, what do you do about it?

Allen: I know one thing you’ve told me is that it’s, you know, frequently in healthcare because, obviously, people that work in healthcare are empathetic and they care about their patients, and they get into those situations. Sometimes it’s, you know, “Look, can I get you a … get you some jello or a sandwich,” thinking that that somehow’s going to solve the problem.

Joel: Often we’ve been actually trained to reinforce those bad behaviors. You know, I’ve seen the cycle happen, you know. A patient will, or a visitor, you know, will lead outside of a door at a patient’s room and yell down to the nursing station, you know, “Get your behind down here,” and they’ll come running.

Allen: Yeah. Exactly.

Joel: When people are angry, you know, give them a … We want to deal with the anger, we want to hear their problem, we want to do service recovery for things that we do, but when people are being treated with disrespect and aggression, if we reward that, we’ll see more of it.

Allen: Yeah. You’re the nurse that thought part of her job was to be abused, in so many words. So, where did it go from there?

Joel: Well, where it went from there is we met with the family, set limits on behavior, just, you know, kind of setting the social contract, helping, you know, that family understand that we want his child to be able to visit with his father, and we just set up a schedule. We did some supervised visits. We put a way that he could have an emergency contact if something went bad during where he wasn’t scheduled.

setting the social contract, helping, you know, that family understand that we want his child to be able to visit with his father, and we just set up a schedule. We did some supervised visits. We put a way that he could have an emergency contact if something went bad during where he wasn’t scheduled.

Joel: So, we were able to manage that with the understanding that … what the expectations were. He got it at that point. So, he wasn’t a perfect angel, you know, but we were able to see to people’s safety.

Allen: Well, there was probably times where, hopefully, that nurse got the message and understood that there’s times when, you know, it’s patient’s gone a little too far and you got to set boundaries [crosstalk 00:20:01]

Joel: It opened the conversation and then we were able to do some training with that staff, that seemed to, you know … The benefits of that is not only that we see a better relationship between patient and provider, but whether people like to admit it or not, if a healthcare provider, a nurse, any other type of provider, is in fear of, or even doesn’t like their patient, they’re going to spend less time with them. Right? Maybe even make more mistakes while they’re worrying about watching their back.

Joel: So, it even affects patient outcomes. So, if we’re not good at this, you know, it affects the bottom line because, you know, people give you bad patient satisfaction surveys, you know? That’s something that they worry a lot about in hospitals, is … and nurses bring that up a lot. You know. I can’t tell someone, you know, not to scream at me and call me names because they’ll give me a bad satisfaction survey.

Allen: Exactly, exactly.

Joel: If you let them abuse you, you think they’re still going to give you a good one? You know?

Allen: Exactly. Right. Right.

Joel: That’s just it. What we’ve tried, and killed them with kindness, that’s something you hear a lot in healthcare. You know? And just like I know I bring the parallel up, but it’s really striking if you study both cycles of violence.

Joel: If you look at domestic violence relationship and a friend of yours came and said, “Hey, I’ve been dating this guy and he seemed like a nice guy, and he had a couple of beers, and he shoved me and called me the B word,” you wouldn’t tell her to kill him with kindness.

Allen: Exactly. Yep.

Joel: You’d say, “Get safe and get help.” But that’s the same advice that nurses give to each other day in and day out at every hospital, emergency room, a doctor’s office, across this country. They’ve heard it in their orientation training. They’ve heard it from their mentors, their supervisors, and it’s a mantra that has contributed to the levels of violence in healthcare.

Allen: Yep. So, I’m hearing two things here, Joel. So, on one hand, right, we need to be aware that just because, you know, you’re in a hospital, that doesn’t mean it’s an environment where people should be allowed to abuse each other.

Joel: Right.

Allen: It’s like any other work environment, that people should treat each other with dignity [crosstalk 00:22:44]

Joel: As a consumer, I especially get it. Healthcare’s a high stakes profession. Trust me, at the local department store, the big box store, the customer’s always right, kill them with kindness, the same advice they’re hearing day in and day out. But going to buy your television at the big box store and call them a bunch of dirty names, and yell at them, and threaten them, and see how fast you get kicked out and the police are called.

Allen: Exactly.

Joel: Right?

Allen: Yep.

Joel: I understand you can’t take a cancer patient, you know, or someone in the emergency room, having a cardiac incident, and throw them into the street. Not suggesting that. We are …

Allen: That’s what I was going to get at, Joel, is that there’s boundaries, right, and in a retail environment, like you just said, you just kick them out and they don’t get back in, and everybody knows who they are, and that’s it. But in healthcare, you really don’t have that opportunity.

Allen: So, on the other side of the equation, you need to set the boundary but you need to do it in a way that works, which gets back to your strategies about, you know, how do you do this? One is you got to be aware that you need to set boundaries. You can’t let people abuse you. You can’t hit, get pushed and shoved, and not do something about it. You don’t want to be the victim and say, “Oh, you know, let me get you some jello or a sandwich, or a cup of coffee, or whatever.” [crosstalk 00:24:03]

Persuasion + Redirection

Allen: So, you need to deal with it but the question is how do you deal with it? Because you can, obviously, deal with it in a way that would make it way worse.

Joel: Yeah, well, in healthcare, there’s … When it comes to the consumer, the client, the patient, there’s kind of been an all or nothing mentality. Either we have to treat them and take whatever abuse they have to dole out, right, or we have to cut them off, right, send them to another hospital.

Joel: I’ve been in those meetings. I’ve helped draft those discharge letters that say, “You’re not welcome at this hospital.” I’ve done them for entire hospital systems that were so big that you lost access to half the healthcare in that state.

Allen: Oh, wow. Yep.

Joel: Because, you know, you just couldn’t get that behavior under control. But what we’re not good at is persuasion, and this is one … redirecting those behaviors so we set the social contract at the outcome, when they’re walking in the door, going, “What’s taking so effing long?” We’re saying, “You know, sir, I understand this is difficult, you know, we have sicker patients coming in by ambulance through the back. Let me take a look and see if I can make you more comfortable for the time being, but can I ask you, please, not to yell and curse? I’m going to treat you with respect, and I’m going to ask you to treat me with respect,” that sort of thing.

is difficult, you know, we have sicker patients coming in by ambulance through the back. Let me take a look and see if I can make you more comfortable for the time being, but can I ask you, please, not to yell and curse? I’m going to treat you with respect, and I’m going to ask you to treat me with respect,” that sort of thing.

Joel: Setting that contract, because if we just absorb that behavior, it’s encouraging more of it. Because it’s a gateway behavior, it builds. Starts with the yelling, then goes to the threatening, and then if they’re going to, you know, demean us, yell at us, threaten us, then why not hit us? Again, just like a domestic violence relationship. But we don’t have to be stuck in that cycle. We have to learn how to redirect and persuade.

Joel: Persuasion, oddly enough, and I don’t think it’s just healthcare, because it’s had a big impact on a lot of professions, such as law enforcement and corrections, and education, and other fields, is helping. Setting the social contract and using persuasion. Because if we were better at persuasion, then maybe almost one third of family practice physicians and pediatricians wouldn’t have admitted to prescribing antibiotics when they knew it was contraindicated, when they knew that it was harmful to the health of their patient, and harmful to the public health.

Joel: Almost one in three admitted to that. Right?

Allen: Well, and Joel, as you know, my background is from years and years ago, but I was a hospital pharmacist, dealt with it all the time, it drove me crazy. This is every 10 years, you know, there’s … It becomes the hot, new thing. [crosstalk 00:26:45] We knew that 40 years ago.

Joel: You must have heard the news, right?

Allen: Oh, 40 years ago. This is not a new problem.

Joel: Yeah, and what were the reasons that prescribers would give someone antibiotics, even though they knew it was harmful? What were the [crosstalk 00:27:07]

Allen: They don’t want to deal with the conflict. You know, it’s whatever the output, you know, they don’t want the patient unhappy. They don’t want the patient going somewhere else. They want to avoid the conflict. They don’t want to have to deal with the issue. They go, “It’s just easier to write the prescription out and get the guy out of here.”

Joel: So, what do we got now? Right? We know it’s contributed to … I shouldn’t say know. I’m not a clinician. But the common wisdom would be this must have contributed to the super bugs and antibiotic resistant strains that we’ve seen crop up over the past few years, is when you’re giving … you’re overprescribing antibiotics, you know, that’s … They say that’s the main [crosstalk 00:27:53]

Allen: Joel, as you know, it’s a topic for a whole nother podcast, but, obviously, it impacts the whole opioid crisis that’s going on, right? I mean, it’s the same underlying issues happening, where there’s reasons why that doctor is prescribing another opioid prescription, and it has a lot to do with what we’re talking about here.

Joel: Yeah, and I sympathize with that. You know?

Allen: Yeah. Oh, yeah.

Joel: I understand but, you know, to help people understand, and I’ve had to do this, you know, with physicians, you know, even in the medical college where I did a little workshop, is helping them understand how do you do persuasion? You know, how do you, you know … How do you explain to them that the antibiotic is harmful and this is why?

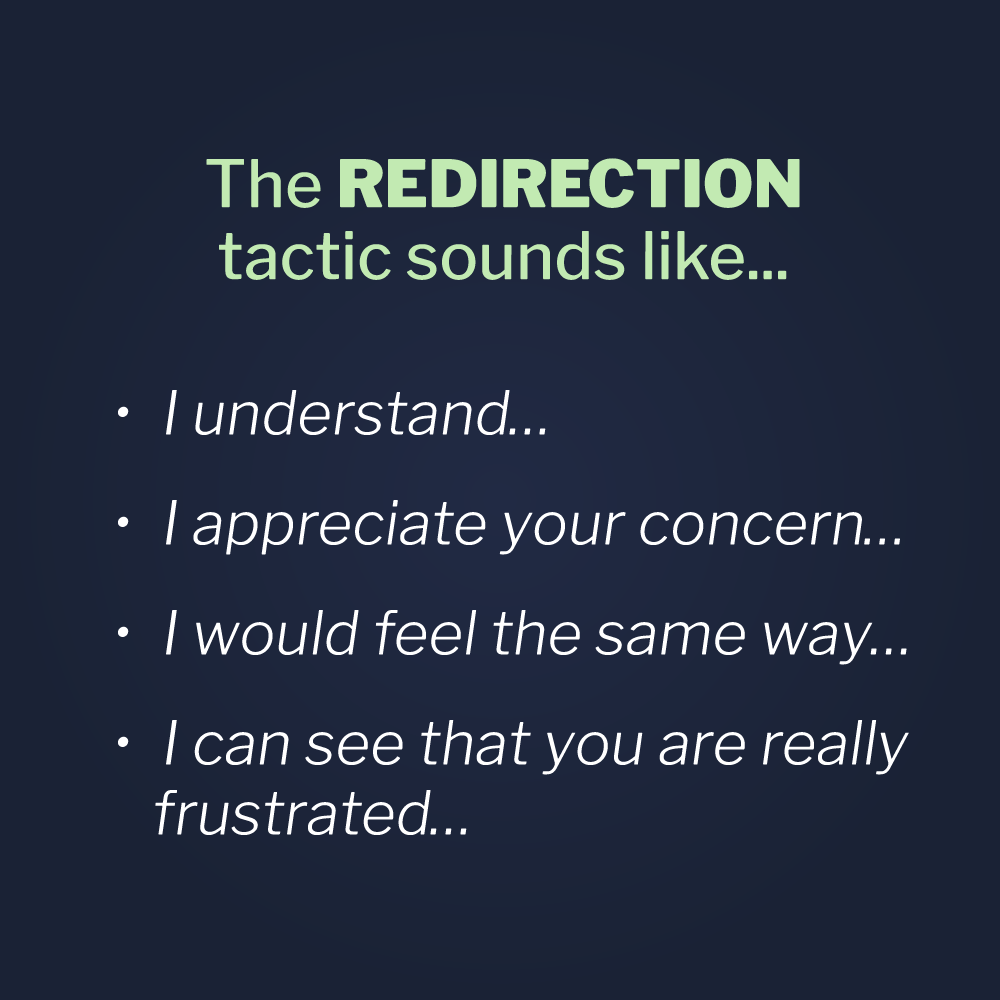

Allen: Exactly, and do it in a way that works. Joel, just so we … Because you used the term, and it’s a term that I certainly understand, but I wanted to spend just a minute on it, is you used the term redirect first, and then now we’re talking about persuasion.

Joel: Yep.

Allen: Let’s go back and just spend a minute on redirection, because, as you know, that’s one of our very specific tactics on how to deal with abuse.

Joel: Yep.

Allen: You gave an example of it, but let me … I’m just going to take that example and break it apart a bit.

Joel: Okay.

Allen: Is that people want to, you know … You were saying, you know, whatever the guy’s on you, about whatever, and you’re going, “Well, first, let me acknowledge that I heard you. I understand where you’re coming from.” I can’t remember the exact words you did, but it certainly is, “I was listening.” I go, “You know, I feel good about that. This guy’s listening. He’s, you know, concerned about my situation. He’s acknowledging my issue here.”

Allen: However, then you quickly went to, “But at the end of the day here, we still have to get back to the point and the issue. I’m not going to let you just continue to abuse me here. I’m willing to acknowledge your concern and your, you know, whatever, anger, whatever it is, but we still got … I still have a job to do, and we’ve still got to get back and deal with whatever we’re dealing with.”

Joel: Yeah.

Allen: So, you know, the whole redirection has two steps, right? Acknowledge their concern, and there’s a variety of ways to do that, and then there’s let’s get back to the issue to make sure they know you’re serious.

Joel: Yeah, the message is, “I hear you and I want to help, and I’m doing the best I can for you right now.”

Allen: Yep.

Joel: Then redirecting them, you know, to what’s important. “However, this has to be a safe and comfortable environment for all patients.” That’s the expectation.

Joel: You know, the behavior you allow is the behavior you’ll get. You know? There’s lots of parallels to that outside of healthcare. You know, like a cell phone in a movie theater. Took a while for everybody to get that. You know, working in a hospital a few years back, and I’m sure most people can relate to this, especially if you’ve worked in hospitals, when I first worked in a hospital, there was a smoking room in the hospital. There was one for staff, and maybe one for patients, and then sometimes they were just combined. It was a normal social behavior at the time.

Joel: Then a few years later they moved them outside. Right? Then they …

Allen: Joel, you probably don’t remember, but I was actually involved in the amount of money they … This hospital I was in was in Philadelphia, but the amount of money they spent to put in the air ducts and stuff to make sure the smoke got out of the room and all that, just so somebody could smoke. You know? It was [crosstalk 00:31:34]

Joel: Air filtration systems and all this [crosstalk 00:31:39]

Allen: I had a lot of money just so somebody could smoke in a room inside the hospital. Those days are passed, but …

Joel: It passed.

Allen: Yeah.

Joel: I’m trying to get to a … The point I’m trying to get to is, you know, first they went from inside the hospital to a smoking booth outside the hospital, to eliminating, to banning smoking on campus, period. Probably the pushback we heard most often, right, because I was involved in some of these projects, was, “Patients will never accept this. You can’t tell somebody whose, you know, wife is sick in the hospital, or they’re having a baby or whatever, they can’t go outside and smoke.” Right? “You can’t do it, can’t do it, can’t do it. It’ll never happen.”

Joel: Within a couple of short years, it did happen.

Allen: Yep.

Joel: Right? The place didn’t fall down, like everyone predicted. Right?

Allen: Right.

Making Violence incompatible with the environment

Joel: When they first banned smoking in prisons and jails, they said, “The prisoners will riot! They’ll … It’ll be a blood bath if you ban.” There was no blood bath. Right?

Joel: Helping people understand that you can affect … People will adapt to the environment that they’re in. If the environment that you’re in is accepting of a certain behavior, guess what happens? You’re going to get it. You’re going] to get the behavior you’re accepting of. Right?

Joel: Then when there’s lots of things that hospitals can do to do effective persuasion. Persuasion is helping people understand the context, right, in their behavior, right, and the expectations. Then if that doesn’t work, it’s offering them choices. This is where they get, you know, a good choice versus a bad choice, and empowering them to make that choice.

Joel: In the vast majority of cases, they will take the good choice, right? People say over and over again, “Hey, if you tell someone not to do this or to do that, they’ll just, you know, tell you to jump off a pier.” But most of them, and even if you ask them, like say, in a training, “Have any of you ever asked somebody to stop doing something inappropriate,” most of them will say, “And the person responded with, ‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean that. I’m just upset.'” Right?

Joel: Most of them in that class will say, “Well, yeah. That’s happened to me. I’ve had that.” Well, all of those that are saying yeah and nodding their head yes are exploding another very destructive myth that’s in healthcare that contributes to all this violence. That myth is that if you say something, it’ll make it worse. We have to say something when these things come up, because if we don’t, the nonverbal message of silence is, “It’s okay to abuse me. It’s okay to disturb other patients. It’s okay to threaten people.”

Joel: That’s something that we’re really not good at in healthcare. It’s because of the high stakes thing, and I get that. But there are things that we can do to persuade people. There are bad options for people. You have to be willing to execute those options, and that’s something we’ve been not really good at in healthcare. Imagine you were cussing out a nurse, or sexually harassing a nurse, or something like that, which is a common complaint in hospitals. Being flirty, being inappropriate.

Joel: All the excuses came from the family, “Oh, that’s just Uncle Jim. That’s just how he is. He’s harmless. He doesn’t mean anything by it.” So, our message to the nursing staff, the female nursing staff, then is, “Well, you have to accept this. He’s just being Uncle Jim. I know it’s inappropriate, but he’s sick and he has to be here.” Imagine if you’re able to say to that family, “We know that’s Uncle Jim, but that’s not allowed here. So, Uncle Jim has to get his sexual harassing behavior under control, and under control now, or he’s going to lose his visitation privileges.” Period.

Allen: But, Joel, as you know, I’ve been asking this question for the last 10 years, since we started the company, if you ask people, “You know, what do you do if somebody’s in your face and they’re abusing you, yelling at you, screaming, cussing, whatever?” Most people just stare at you, going, “I don’t know.” Right? Then what happens is they can make it worse by getting too assertive, too aggressive, whatever, and, you know, acting out, because they don’t know how to respond.

Allen: I think the bigger issue is the second one, which you ask people … If you ask somebody to do something, they say, “I’m not going to do it,” then what do you do?

Joel: Well, yeah.

Allen: It’s rare that I find anybody that goes, “Oh, yeah. Well, I would go through this little process.” As you’re describing, there’s a very specific three step process that, most of the time, will get people to go along with the program.

Joel: First, you have to train people. You know, I get very passionate about this subject, Allen, so, I can get pretty animated. You know, all behavior is equalized. So, if someone’s being aggressive, we should never be aggressive in return. We have to maintain our professional language. We have to model the behavior we want to see.

Joel: If they’re yelling, we want to get quieter. If they’re crowding, we want to step back. Many of the physical alternatives and things that we train, you know, as you know, are the one handed stop sign, the two handed stop sign, the emergency time out, proxemics, maintaining our professional distance, that maintains safety in that. The first responder philosophy is, “When are we in danger and shouldn’t have this conversation right now, and when do we need to contact the right people to support us.”

that. The first responder philosophy is, “When are we in danger and shouldn’t have this conversation right now, and when do we need to contact the right people to support us.”

Joel: It’s all part of a system that people have to be trained to do. Where we’ve seen it done, where hospitals have dedicated themselves to this training, we’ve seen, you know, some impacts that are positive, measures that are even extreme, you know. The reductions in assaults on staff, improvements on the morale. [crosstalk 00:37:50] Positive patient satisfaction surveys. You know. It’s just this is such an intimate relationship between provider and patient. We have to understand how to communicate and how to set limits, and how to persuade, right, and know when to get safe, right.

Conclusion

Allen: Well, you said it back early in our discussion here, is that people just aren’t trained on this. It’s like, you know, how do you … When were you ever trained on how to talk to people? [crosstalk 00:38:24] Other than some good manners stuff, but this is … Joel, I think we’re … Here’s what I’d like to do, is, I think this has been a great discussion to identify the problem.

Allen: I think we’ve figured out that there’s things you can do, that you can’t just let things happen. You can’t just ignore it and assume that it’s part of the job. You need to take action, but you need to take action in a defined way, or you might make it worse. Right?

Allen: So, why don’t we kind of wrap this up and, maybe, the next time we’re on, let’s dive a little further into this persuasion approach about, you know, how do you take somebody that says, “I’m not doing this,” and what do you do to get them to go with the program?

Joel: Yep.

Allen: Without, you know, calling security and asking the guy to get taken out of the building.

Joel: Yeah, that’s what we do, Allen. You described it perfectly. We go to zero or 60. [crosstalk 00:39:22] Nothing in between. Zero or 60. Give in or call security. The paradigm has to change.

Joel: Where we’ve changed it, we’ve seen really positive results.

Allen: Well, as you know, one of our clients, we just heard this last week, was … You know, they have an outside security team, which is very common, one of these private security companies that deals with security, and then internally, they have people that have actually been trained by us. You know, it’s just a huge problem because the security person shows up and doesn’t know how to deal with that patient appropriately, and then things get worse.

Allen: So, they’re actually saying, “Yeah, we’ve got to find a way to bring all our security team inside so we can train them, and so everybody’s dealing with people in a consistent manner.” [crosstalk 00:40:12]

Joel: You know, inconsistency is the enemy of peace. I’ve seen it go both ways. I’ve seen it where the security staff has been trained, right, and the medical staff shows up and then it goes south. I’ve seen it like this, where the medical staff is well trained and the security staff shows up, and it goes south, because, you know, the lack of consistency in approach, the lack of level of competency in the training and supervision.

Joel: Most violent incidents can be traced to some form of inconsistency.

Allen: I was pretty sure when I said inconsistency, you would … That’s one of your more famous quotes, right? “Inconsistency is the enemy of peace,” and it’s … We’ve learned it’s so true.

Joel: Yeah. [crosstalk 00:41:04] Lots of bumps and bruises to learn that over the years though.

Allen: Well, maybe the next time when we talk about persuasion, I think you have a great story about that, both about the impact of being consistent and then I can remember another one about, you know, what can happen if you’re inconsistent.

Allen: So, let’s deal with that the next time. Appreciate you spending the time. It’s always fun talking to you, Joel. I always learn something new. We’ll do this again.

Joel: Thanks, Allen. It was fun. Looking forward to the next one.

Allen: Yep. Okay. Take care.

Joel: Bye.

Allen: Bye bye.