(Note: Names are fictional and do not identify the actual individuals in the article)

Have you ever been corrected for a decision you made, but you knew in your heart that it was right? Did you struggle with explaining why you made the right choice?

Have you ever known someone who was very decisive, but seemed to make a lot of poor, bad, or unfair decisions? Or how about someone whose decision-making was always suspect, by appearing judgmental or biased? Were they trained to treat all people equally with dignity and respect?

No one likes others questioning their decisions, but when you start to question your own judgment, you are in a bad place. You know you’re in trouble when the best answer you have for making a questionable decision is: “Well at least I made a decision.”

For this, you must have the proper training and the ability to articulate why you did what you did – when you were right in doing so!

Most people have trouble making decisions under pressure, but decision-making is part of professional life and it’s difficult to escape the responsibility of having to do so. Some people fear decision-making so much that they avoid it by standing in the shadows and forcing others to make them; or worse, by ignoring situations they know should be corrected, but won’t risk being judged for their actions.

A Lesson in Decision-Making

In this article, I will give you an example of a time when I was forced to make a decision that I knew I’d likely be judged for, but was confident that I was taking appropriate action. I will give you an actionable method to improve your decision-making by ensuring your decisions are consistent, unbiased, and defendable – no matter what the outcome is.

Would you judge a member of hospital staff for kicking out the mother of a cancer patient? Before you answer too quickly, read on.

Many years ago while working as a security supervisor at a medical center, I was forced to ask the mother of a cancer patient to leave the hospital while we cared for her child. As you might imagine, a lot of people questioned my decision. In fact, when I was initially called by my director to meet with the patient’s physician, he said, “Watch yourself. That doctor wants your head on a platter.” Confident that I had made the right decision, I immediately responded to the patient’s unit to meet with the doctor.

When I arrived at the unit, the doctor greeted me by the elevator, loaded for bear. Before I could even say hello, she asked sternly, “Are you the guy who kicked my patient’s mother out of the hospital?”

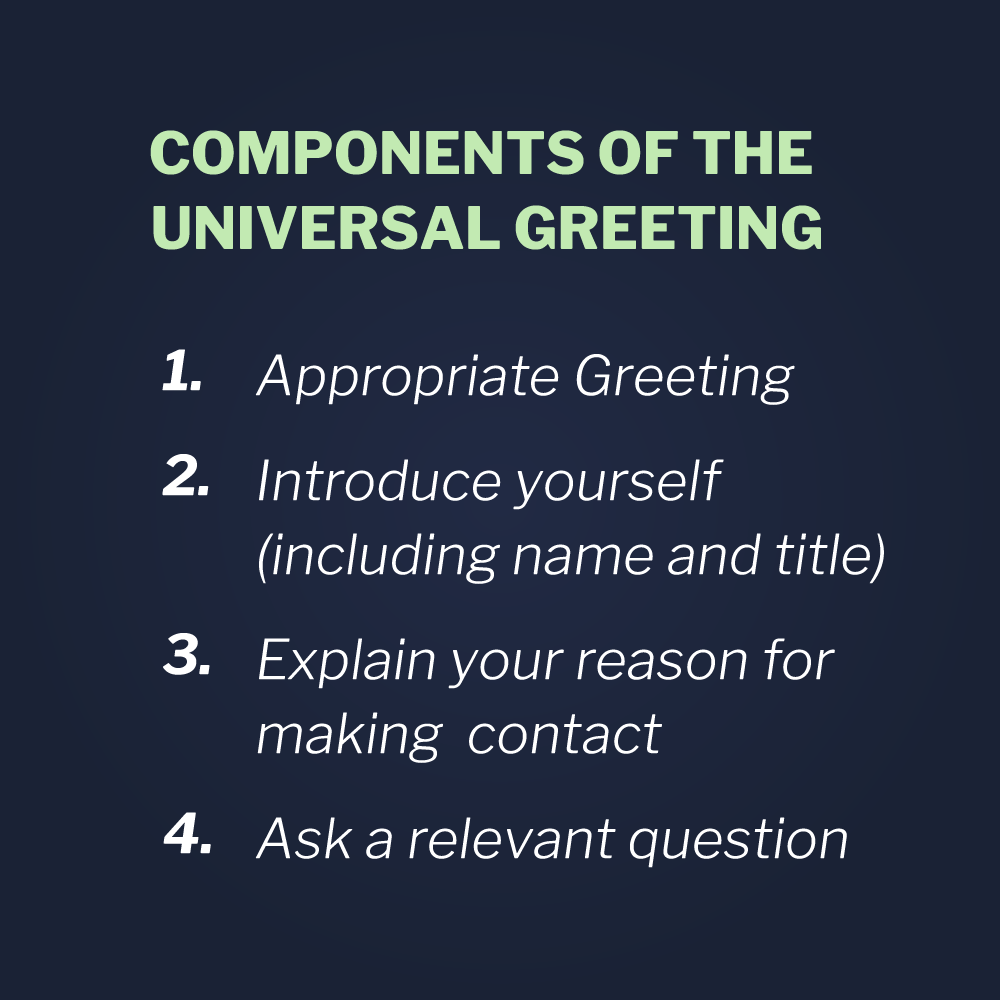

I answered her calmly in an effort to de-escalate her, while opening with a Universal Greeting, ensuring that I would be professional and trustworthy, by removing any doubt in the doctor’s mind regarding my intentions.

I would be professional and trustworthy, by removing any doubt in the doctor’s mind regarding my intentions.

Universal Greeting

- Appropriate Greeting

- Name and Affiliation

- Reason for Contact

- Relevant Question

“Hello, Doctor Smith. I’m Joel, the Security Supervisor for the third shift. The patient’s mother was creating a disturbance, so regrettably I did have to ask her to leave the hospital for the night. If you have any questions about what happened, I’d be glad to explain my decision.”

“That woman’s child has cancer! Don’t you know that?” she asked.

“Yes, I am aware of that. The decision I made was based on the interest of all the patients on the unit, including that mother’s child. May I explain why?”

Still visibly angry, the doctor said. “Ok, so what happened exactly? Explain yourself!”

“The nursing unit dialed the campus emergency line around midnight to let us know that a mother was screaming and yelling on the floor. They also complained that she was waking and frightening the other patients and parents. When we arrived, we could see the mother standing in the hall shouting and cursing. Also, other parents were standing outside their children’s rooms and were visibly concerned about the commotion,” I explained.

“So did you try and reason with her?” the doctor sternly interjected.

“Yes doctor, I did,” I replied. “I approached her, while allowing her plenty of space, and introduced myself. I told her that I could hear that she was upset. I asked her to accompany me to a conference room to talk, so we wouldn’t disturb the other patients.”

“Well then, so what did she say?” the doctor asked.

“She said she didn’t care about any other people’s kids and continued to shout and curse,” I replied.

“So you kicked her out?” she asked.

“No, we didn’t ask her to leave yet,” I replied. The doctor looked at me with a more curious look now, so I continued.

“I explained that the hospital needs to be a safe and healing environment for all patients and families, and that we were just as concerned that her daughter get her rest and feel comfortable. I explained that I would contact the on-call administrator or the on-call physician, if necessary, to address her concerns, but I asked if she would please stop waking up and frightening the other patients.”

“That didn’t work on her?” the doctor asked.

“Regrettably no. She continued to yell and curse loudly,” I replied.

The doctor’s expression softened. “Ok, I get it. You tried your best I’m sure. So that’s when you decided to throw her out. Unfortunate, but what else could you have done?”

“No, we didn’t ask her to leave yet,” I replied. The doctor looked puzzled now.

“What happened then?” she asked.

“Well, the social worker arrived on the unit to help as we requested. When he tried to introduce himself, the mother yelled and cursed at him, as well. So I continued to try and persuade her, as we are trained.” Now the doctor looked really intrigued.

“So how does that work?” she asked.

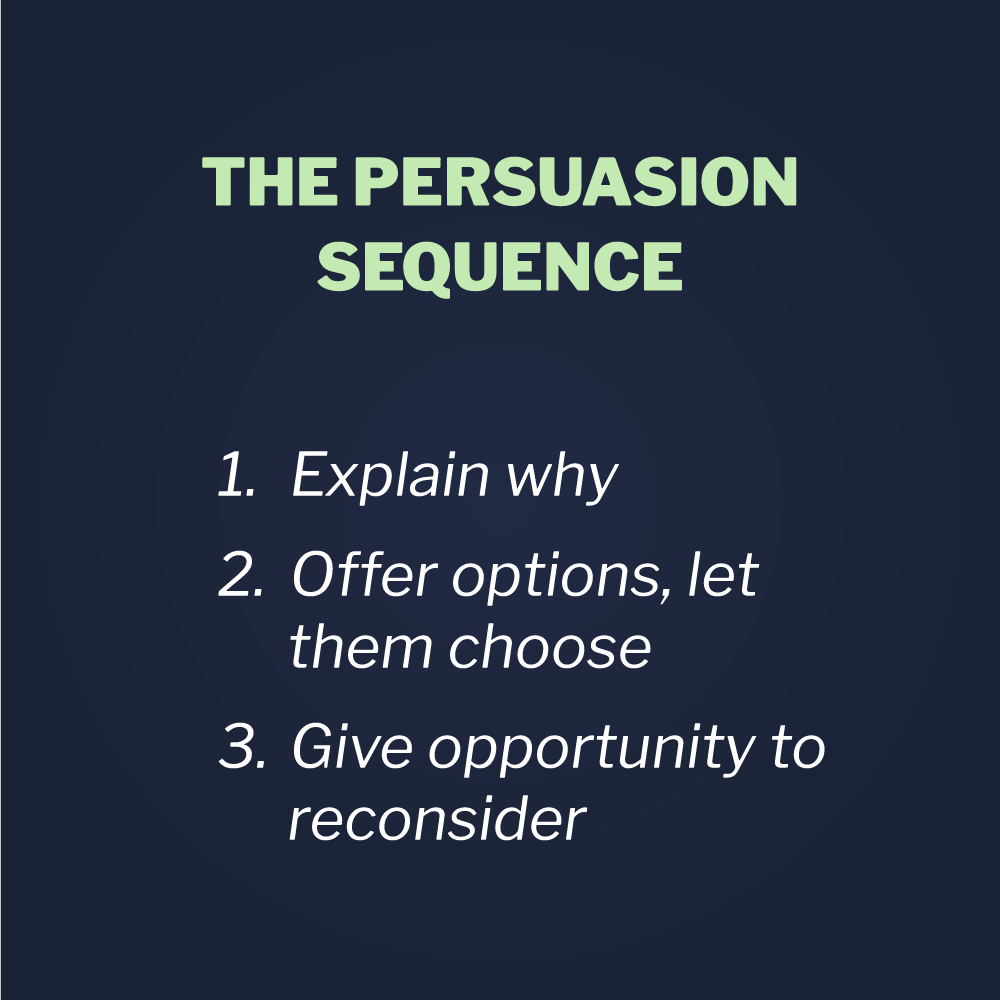

“Well, after we introduce ourselves, we explain why we are asking them to cooperate with us. We explain the relevant policies and the rationale for them. Then we attempt to confirm their understanding of the request. Since that hadn’t worked so far, it was time for me to offer her some options and let her choose.”

“How did you do that?” she asked.

“First, we are trained to tell people their good options, so we don’t sound like we are giving them an ultimatum. I said she could talk with the social worker to address her concerns. If she had medical concerns, we could call the on-site staff physician. Finally, if she had a complaint about how she and her daughter were being treated by the staff, I could call patient relations and ask a representative to respond.”

Then I explained to the doctor how I presented the less desirable options, by letting the patient’s mother know that if she refused to stop yelling and disturbing the other patients, we would have to ask her to leave. I also told the mother that it was hospital policy that quiet hours are to be observed by everyone after 8 p.m., and that offensive and threatening language was not tolerated at the medical center.

“After all that, I reminded the patient’s mother of her better choices, by saying that I would rather not ask her to leave and asked again if she would come with me to the conference room.”

“Okay, what did she say to that?” asked the doctor.

“Unfortunately, she yelled and cursed at me. Giving people their options usually works, but not always.” I replied.

“Okay, okay. I get it. So you threw her out then?” said the doctor.

“No, I didn’t ask her to leave just yet.” I said. The doctor really looked puzzled now.

“Well, why not? Honestly, at that point, I would have,” she replied.

“It’s how we are trained,” I replied. “First we are supposed to thoroughly explain why we are asking someone to do something. That works on most people. When it doesn’t, then we are trained to offer the individual their choices and let them choose. Even when people are really upset, they will usually take the good choice. But for those few that you just can’t persuade, we are trained to give them an opportunity to reconsider. So finally I asked the patient’s mother if there was anything I could say to get her to stop yelling and waking the patients, so I could help her with her concerns. And even after all that, she yelled and cursed loudly.”

“So that’s when you asked her to leave?” the doctor asked.

“Yes, doctor. That’s when we asked her to leave. I escorted her out of the building, and made certain that she made it safely to her car. After that, the social worker is responsible to contact her to set limits on future behavior, offer counseling, and make visiting arrangements.”

To that, the doctor offered her hand for me to shake, saying “Well Joel, you’re a nicer person than I am.”

The above example illustrates how The Persuasion Sequence is about far more than just being effective in generating cooperation. It also covers us afterward, when people question our actions and decisions.

generating cooperation. It also covers us afterward, when people question our actions and decisions.

The Persuasion Sequence

- Explain Why

- Offer Options, Let Them Choose

- Give Opportunity to Reconsider

Communication tools, like The Persuasion Sequence, ensure that our staff make consistent and justifiable decisions, by demonstrating that the person we were trying to help was given every opportunity possible to cooperate with our policies and requests. It’s just another step in building consistent decision making for both ourselves and others. Once mastered, it becomes a template for articulating the justification of our in written documentation, such as emails and incident reports.

Writing a Good Report to Defend Your Actions

Below is an example of how The Persuasion Sequence can be used to frame and document the incident described above.

I arrived at the Cancer Unit at approximately 12 a.m. to investigate the complaint of a mother of a patient waking and disturbing other patients on the unit. When I arrived, I observed a woman, later identified as yelling loudly and cursing in front of the nursing station.

I approached her and introduced myself, using a Universal Greeting.* I asked her to stop yelling and cursing, and explained that she was waking and frightening the children on the unit.

She replied by saying, “$%^& you and %^&* those kids too!”

I then said that I would do everything possible to help her and to please accompany me to a conference room to discuss her issues. I explained that hospital policy requires that everyone observe quiet on all patient units, between 8 p.m. and 8 a.m., so the children could get their rest and not be disturbed. Then I asked her if she understood the policy.

She replied, “I don’t give a $%^&* about your #$%^& policy!”

I then offered her some options, saying that I could call the on-call physician, social work, or patient relations to address her concerns immediately, but if she didn’t stop disturbing the patients, we would have no choice but to escort her out of the hospital for the night.

She replied, “I ain’t #$%^& going anywhere!”

I then asked her, “Is there anything I can say to get you to stop creating a disturbance and let me help you, instead of asking you to leave for the night? Please work with me.”

She said, “Go #$%^& yourself.”

At that point, I advised her that we had no choice but to escort her off the unit. I offered her a consultation with a counselor and she declined, saying,

“I’m just exhausted, frustrated, and want to leave.”

We escorted her to her car, due to the late hour, and she left the property for the night. I then offered her positive closure to the incident by saying,

“I’m sorry things ended this way, Mrs. Baker. I hope you come in tomorrow and meet with patient relations so they can hear your concerns and you can continue visiting your daughter.”

I then advised Mrs. Baker that patient relations would be in contact with her tomorrow and that she could call the unit as needed for updates on her daughter’s condition.

showing respect while making Tough Decisions

The following day, the mother met with patient relations and began visiting her daughter again. Even though there had been a few previous unreported incidents involving this mother, there were no more reported after this incident.

To my surprise, the mother wrote a letter to the hospital president, thanking me for my intervention, saying that she wasn’t herself that night and that I treated her with respect. It was an odd thing getting a “thank you” letter for throwing someone out of a hospital, but it really is true: it’s not what you say, but how you say it. But outcomes like this are usually most heavily influenced by proper closure, no matter how the situation ends.

Closure is another important method involving communication, documentation, and debriefing that we train at Vistelar. It’s how we end an encounter on the best possible footing, so we are prepared when that person complains or when others question our actions. It also increases your safety – and that of your peers – when you or they encounter that person next time.

Every one of Vistelar’s verbal communication tools can be applied to enhance report writing, giving them yet another valuable benefit. By following our training, we can ensure that we get better and more consistent results. And, even when things don’t end as we would have preferred, we can still justify our decisions; because we are responsible for the process, not for the outcome, when we follow our training.

Training to respond, follow-through, and report need to be interrelated in a way that makes sense, while being more effective, safer, and professional all at the same time. As one of our founders Gary Klugieiwcz always says, “It’s not enough to do the right thing. You must be able to explain why it was the right thing to do based on your training, experience, and the facts of the situation.”