This manual is a guide for healthcare and social services professionals. It covers information about how to work in the community and conduct safe and effective home visits.

This is the manual for the on-site and virtual instructor-led training and online on-demand courses offered by Vistelar

The skills learned in this training program have application when interacting with someone who is

- a possible threat to your emotional or physical safety

- experiencing an inability to cope with a situation

- displaying gateway behaviors

- questioning or refusing a request

- confronting you with shouting, anger, or ranting

- exhibiting at-risk behaviors

- demonstrating aggressive or violent behaviors

Please note that the local jurisdictions of healthcare and social services home-visit organizations may vary by state statute and organizational policies and procedures. While the information in this manual should have universal application, your laws, policies, and procedures should always take precedent.

If you are responsible for the development and implementation of an organization-wide workplace violence prevention program (OSHA – Occupational Safety and Health Administration), the information in this manual about keeping healthcare and social services workers safe will prove valuable. However, obtaining additional information beyond what is included in this manual is recommended, such as

- organizational rules and procedures related to

- maintenance of physical security

- emergency preparedness

- chains of communication during and after an incident

- post-incident analysis, reporting, and record-keeping

- protocols for when law enforcement is involved

- analysis of technology and vulnerabilities related to physical and procedural security

- staffing, training, and deployment of security personnel

- criteria for hazard prevention and control

- policies and procedures for active shooter/assailant response

- personal safety, protection, and security training

Who Is Vistelar?

Vistelar is a conflict management training and consulting institute focused on addressing the entire spectrum of human conflict, from non-escalation to stopping the threat.

We offer a wide range of training programs for building respectful and safer work environments that address how to

- provide better customer service

- predict, prevent, and mitigate conflict

- avert verbal and physical attacks

- de-escalate resistance, anger, and abuse

- control crisis and aggression

- effectively manage physical violence

We offer training in these nine categories:

- Workplace Violence

- Lateral Violence

- De-Escalation

- Personal Protection

- Home Visitation

- Interventions

- Emergency Response

- Physical Alternatives

- Specialized Public Safety

Vistelar’s methodologies have been proven in real-world environments for over forty years and are the subject of several published books in the Vistelar Confidence in Conflict series.

We offer our training via speaking engagements, workshops, and instructor schools using online, virtual, and in-person methods of instruction.

Our vision is to make the world safer by teaching everyone how to treat each other with dignity by showing respect.

Benefits

After reading this manual, you will be better prepared to maintain your safety in both your work and personal lives.

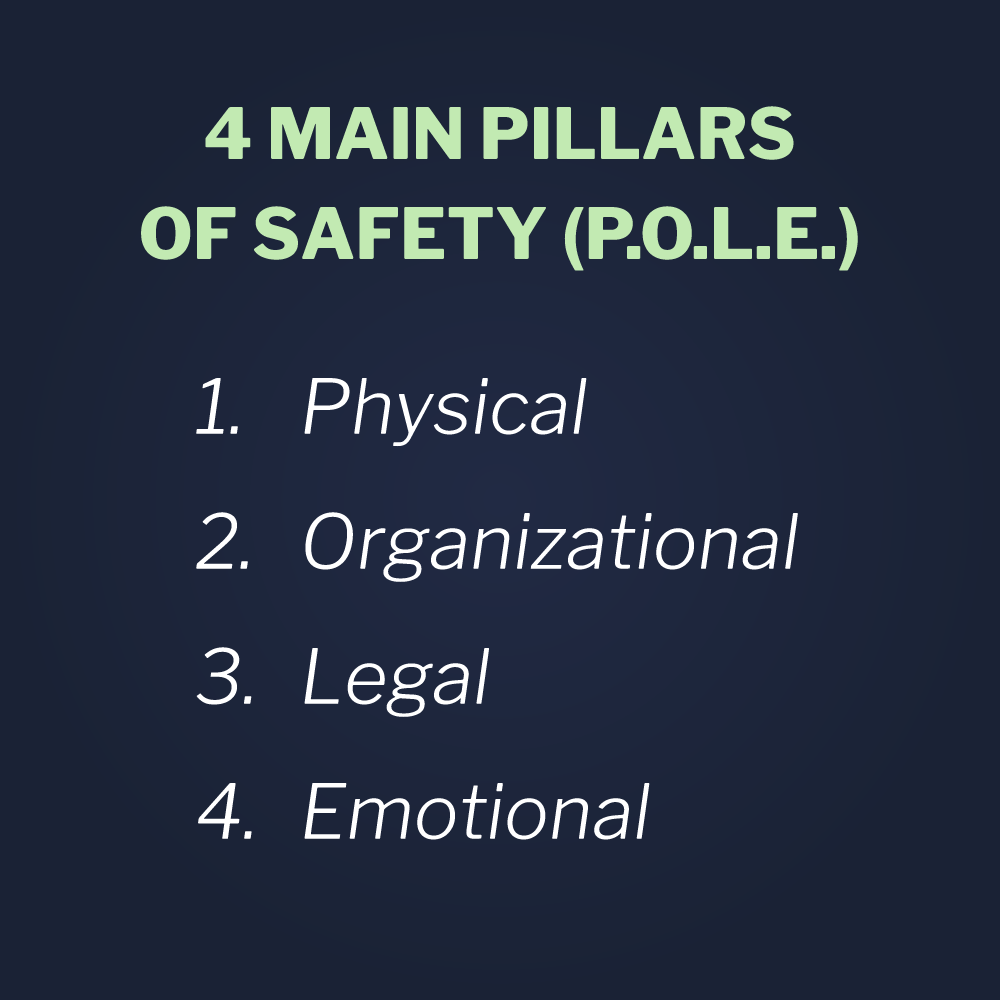

This training program aims to increase safety and improve outcomes in these four areas (P.O.L.E.):

- Physical: improved threat assessment and violence prevention

- Organizational: improved job performance, morale, and collaboration

- Legal: protection from personal liability, career pitfalls, and damaged reputation

- Emotional: stress reduction, improved relationships, self-confidence, and quality of life

You will gain the knowledge, skills, and abilities to

- assess initial client contact and follow-up community contacts for threat potential and peripheral risk

- manage safety at three critical junctures: when approaching a client’s home, interacting at the door, and once inside the dwelling

- prevent emotional and physical violence via the practice of non-escalation

- recognize Gateway Behaviors to Violence and threat indicators that may compromise safety

- end interactions better than as they started and with a positive foundation for future contact

- resolve disagreements and refusals and de-escalate verbal confrontations

- stay safe and promote recovery in crisis situations

- recognize when verbal methods have failed and it is necessary to take further action

- debrief, document, and report violent incidents

The results within your organization will include

- enhanced client satisfaction

- improved client outcomes

- decreased risk and liability

- protected reputation

- less absenteeism and turnover

- fewer worker compensation claims

The results within your team will include

- increased safety

- improved productivity and morale

- more confidence in managing conflict

- better personal relations

- reduced lateral violence/bullying

- less conflict avoidance

Definitions

Physical Assault – To touch another person without explicit or implicit permission or with the intent to cause physical or emotional harm.

Verbal Assault – To attack another person via spoken or written words with the intent to cause emotional or social injury or damage to personal or professional reputation.

Domestic Violence – Acts of physical, sexual, psychological, and social violence that occur as part of familial and personal relationships, such as intimate partner abuse, child abuse, elder abuse, and abuse of disabled family members.

Gateway Behaviors to Violence – Antisocial actions that may or may not make a person feel threatened at the moment but have been shown to be reliable predictors of violence, such as disrespectful actions (shouting, sarcasm, cursing, name-calling, aggressive posturing), veiled threats, and overt threats.

Threat – Any written or oral expression or physical gesture or action that could be reasonably interpreted as conveying an intent to cause harm to persons or property.

Harassment – Threats or other conduct which create a hostile environment, impair organizational operations; or frighten, alarm, or inhibit others.

Mugging – An aggressive assault, usually by surprise and with intent to rob.

Stalking – Repeated and unwanted interfering with the freedom of another person, which places that person in reasonable fear of professional, social, psychological, and/or bodily harm or death.

Weapon – A device, instrument, or substance that is used for, or is readily capable of, causing death or injury, such as guns, knives, clubs, chemicals, electrical stunning devices, and explosive devices.

Improvised Weapon – Any readily available object or substance capable of being used as a weapon – anything that can be thrown or used to strike, club, stab, slash, shock, asphyxiate or burn. Examples include pens, shoes, chairs, eating utensils, computer keyboards, fire extinguishers, bleach, hot water/oil, and aerosol cleaning products.

State of the Profession

Healthcare and social services professionals working in the field operate independently. As such, they establish contact with their clients, set their own schedules, and enter clients’ homes—an unpredictable and unprotected environment. Their clients can be in urban centers, suburban locations, towns, or remote rural areas, any of which may have high-crime elements or histories.

The clients served can have extensive histories of

- trauma and adversity

- relationship difficulties

- lack of trust in healthcare/social services and institutions/systems

- economic stress, which may entail limited access to basic needs

- behavioral and mental health issues (sometimes undiagnosed)

- lack of effective coping skills

- suffering from substance abuse disorders

- criminality

- impulsive behavior

- poor decision-making skills

Typically, home-visitation professionals join their organization with limited life experiences and nominal, if any, conflict management training. The result is inadequate preparation for the stressful circumstances they will face in the field.

Violence against home-visitation professionals can manifest in many forms:

- Weapon use (armed physical assault)

- Unarmed physical assault

- Sexual harassment and/or assault

- Intimidation, harassment, and/or bullying

- Threats of harm or death

- Stalking or displaying undue personal focus (in-person and/or on social media)

- Harmed reputation

- Damaged property

Violence perpetrated on home-visitation workers, in any of the above forms, can exact a heavy emotional and physical toll, both immediately and over the long term.

Beyond violence perpetrated by clients, home-visitation workers – like all workers – face the possibility of a spectrum of conflicts with their fellow employees, such as exclusion, bullying, hazing, or sexually charged remarks.

Outside of work, workers can experience stressors that sometimes overflow into the workplace, such as relationship issues, divorce, child behavior, financial challenges, mental illness, and drug and alcohol addiction.

Beyond the individual, organizations can experience negative behaviors of their clients, such as harassing or threatening phone calls, on-premises violent behavior, and active shooter/assailant events.

Significance of the Problem

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, some 2 million American workers are victims of violence each year. Worker surveys reflect a consensus among employers that the problem is getting worse. There seems to be a general decrease in interpersonal respect and an increase in aggression when conflict arises.

Common threats that have been prevalent for decades (e.g., robbery, gangs, organized crime) continue to exist, but in recent years it seems that people are more easily set off. In addition, almost every interaction is now captured on video, which can show up on social media or the evening news.

Cal/OSHA and NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) have identified the following risk factors that may contribute to violence against workers. Note how many of these factors apply to home-visitation workers.

- Contact with the public

- Exchange money with the public

- Work late at night or during early morning hours

- Work is understaffed

- Enter areas with a high crime rate

- Have a mobile workplace

- Deliver passengers or goods

- Perform jobs that might put them in conflict with others

- Perform duties that could upset people (deny benefits, confiscate property, terminate child custody, etc.)

- Deal with people known or suspected of having a history of violence (e.g., assault, verbal abuse, harassment, or other threatening behavior)

Beyond the heavy emotional and physical toll, violence against home-visitation workers negatively impacts customer satisfaction, employee retention, legal liability, and worker’s compensation claims.

Unified Conflict Management System

This training program is a component of the Vistelar Unified Conflict Management System.

This system addresses the entire spectrum of human conflict, from non-escalation to stopping the threat, and has these attributes:

- Based on the Vistelar 6 C’s of Conflict Management™ framework

- Uses consistent principles, methods, and terminology across all training programs

- Has a systemized structure of methods/tactics represented in simple graphics and reminder cards

- Emphasizes simplicity and universal application with all methods/tactics taught

The result is a system of methods/tactics that are easy to learn, remember, apply, and teach.

The Vistelar Unified Conflict Management System includes these six core training programs:

- Non-Escalation, De-Escalation, and Crisis Management

-

- Supplements: Cognitive Challenges and Mental Illness

- Personal Protection and Safety

- Personal Safety For Home Visit Workers

- Positive Interventions and Stabilization

- Workplace Violence Prevention and Intervention

-

- Supplements: Lateral Violence, Behavioral Emergency Response Team, Active Shooter

- Physical Alternatives (P.O.S.C.™)

-

- Supplements: Impact Weapon (Baton), Chemical Aerosols (OC), Weapons Control

All Vistelar training programs strive to meet these three criteria for evaluating an interaction relative to conflict management effectiveness:

- Look professional

- Demonstrate concern

- Keep everyone as safe as possible

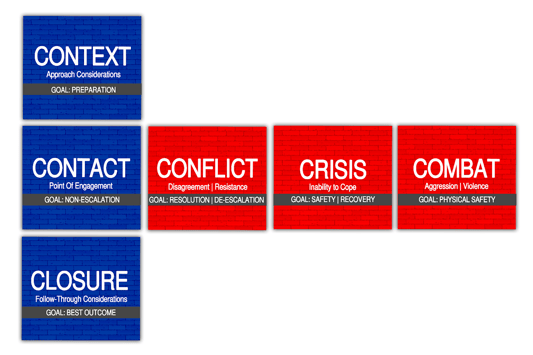

6 C's of Conflict Management

Definition: Framework that provides a means to analyze interactions and determine which conflict management method should be used given the circumstances.

Key Point: Identifying which conflict management method to use to best manage a situation based on the state of an interaction (which “C”)

Maxim: We cannot control the outcome of an interaction, but we can manage the process.

The blue boxes in the 6 C’s graphic describe the three elements of all interactions:

- Context: Period prior to engagement

- Approach Considerations—Goal: Preparation

- Contact: When an interaction begins

- Point of Engagement—Goal: Non-Escalation

- Closure: When an interaction ends; foundation for future interactions

- Follow-Through Considerations—Goal: Best Outcome

The primary goals of these elements are non-escalation (conflict prevention), achieving the best possible outcome, and establishing a positive foundation for any future interactions.

The red boxes in the 6 C’s graphic describe what can happen when interactions escalate:

- Conflict: When an interaction includes refusals and verbal confrontations

- Refusal | Resistance—Goal: Resolution | De-Escalation

- Crisis: When experiences exceed a person’s coping skills

- Inability to Cope—Goal: Safety | Recovery

- Combat: When behaviors are causing or likely to cause physical harm

- Aggression | Violence—Goal: Physical Safety

The primary goals in the face of Conflict, Crisis, or Combat are de-escalation, crisis management, everyone’s safety, and shifting the situation to a positive outcome.

Notes:

- All interactions have a Context, Contact, and Closure element, but only some interactions progress to Conflict, Crisis, and/or Combat.

- All interactions progress from the beginning (Context), to the middle (Contact, Conflict, Crisis, Combat), to the end (Closure).

- The three red boxes should NOT be viewed as a progression—an interaction can escalate from Contact directly to Conflict, Crisis, or Combat.

The goal of almost all interactions is to remain in the blue zone (non-escalation) and to enter the red zone only if others take you there. When that happens, the goal is to move the interaction from the red zone to the blue zone as quickly as possible.

However, there are times when it is necessary to move from the blue zone to the red zone to address an issue and risk refusal or resistance (e.g., address an employee performance issue). Otherwise, negative outcomes can result, such as unresolved conflict, resentment, reinforcement of bad behavior, and even conflict escalation. In these situations, it is important to have confidence in addressing the issue so conflict avoidance does not occur.

Context: Approach Considerations

The goal prior to contacting a client is to prepare for the interaction by identifying pre-incident indicators of violence, assessing risk prior to the initial visit, developing a safety plan, preparing your vehicle and yourself, checking in with your partner, establishing situational awareness, and ultimately deciding whether to proceed.

Pre-Incident Indicators of Violence

Violence in the field rarely occurs in a vacuum. When reviewed after the fact, pre-incident indicators were almost always present. Some incidents are the culmination of multiple warning signals over short or even long periods of time.

Pre-incident indicators prior to the initial contact:

- Previous history of violent episodes, non-compliance, or Gateway Behaviors to Violence, such as shouting, cursing, name-calling, insulting, displays of prejudice, dignity violations, intimidating postures, aggressive positioning, and indirect threats

- Criminal history: violent crime, property crime, sexual offender registry, harassment/stalking order, or violations of court orders

- Social media postings depicting threats, violence, or weapons

- Excessive calls, texts, voicemails, and emails prior to the initial visit, especially if they include Gateway Behaviors to Violence

- Non-compliance with scheduled appointments

- Warnings from family members and associates

Note: if you identify pre-incident indicators prior to a visit, you need to develop a safety plan prior to the visit. See the following section on safety planning.

Pre-incident indicators during community/in-home visit

- Gateway Behaviors to Violence

- Evidence of substance abuse (drug paraphernalia, illegal drugs)

- Acts of aggression (domestic violence, animal abuse)

- Visible presence of weapons in the home or on the client

- Presence of others in the home without prior notification

- References to a recent acquisition or fascination with weapons

- Signs of emotional distress or depressed mood (isolation, withdrawal, poor concentration, crying)

- Shifting blame to others, deflecting responsibility

- Frequent complaints

- Known risk-taking behavior, disregard for personal safety

- Known personal issues (e.g., relationship, mental/physical health, financial)

Assessing Risk Prior to Initial Visit

-

Conduct initial client screening

- Review client file. Any indicators of non-compliance, threats, criminal activity, violent behavior, or dangerous pets are warning signs. If the client has worked with other home-visitation workers, interview them to learn about the neighborhood, presence of weapons, family’s attitudes towards child behavior and discipline, and any other previous issues. Remember, the best indicator of future violence is past violence.

- Criminal record review. Your ability to do a criminal record review will depend on your organization’s internal policies and procedures. The ease of access to individual court records also varies widely between states and jurisdictions. Some states offer free instant online access to adult criminal records. In other states, fees may apply, and access can be significantly delayed. Local law enforcement resources may or may not be of assistance, depending on local laws and your organization’s working relationships with the law enforcement resources in your community. In-person reviews of criminal records at your local courthouse are typically available but can be time-consuming.

- Sex Offender Registry Check. Online sex offender registries are available in all 50 states, all US territories, and Native American-governed lands. In addition, home-visitation workers can access their state court public records. However, it is recommended that caseworkers go directly to the US Department of Justice National Sex Offender Registry (www.nsopw.gov) as it will give them a history from all US states and territories.

- Social Media Check. If allowed by your policies and procedures, check common social media accounts that may have been published by the client. Accounts may be published under aliases, but clients will often publish under their own names. Any mention of the case under investigation should be evaluated for implied or overt threats. Clients who have violent messaging and imagery are also a concern. In addition, look for photos of clients posing with weapons or featuring weapons prominently in their profiles.

-

When calling the client to schedule the initial contact

- Begin contact with a modified Universal Greeting (see a more detailed description of this non-escalation method later in this manual)

- “Good morning

- My name is ____________________.

- May I speak with ________________? I would like to schedule an appointment with him.”

Once you’ve confirmed you are talking to your client:

iv. “I am [position] with [organization]

v. The reason for my call is __________.”

vi. Ask a relevant question

b. State objectives and expectations of behavior

i. Objective for the visit

ii. Ask safety-related questions and state expectations

1. Who else will be in the home? This could be family members, friends, children being

babysat, someone with special healthcare needs, etc. State privacy rules so it is clear as

to who can attend the meeting and your expectations for others (e.g., make

arrangements for babysitting).

2. Does the client have any pets? If yes, ask for them to be secured (e.g., leashed in the back

yard or a room, placed in cage/kennel).

3. Does the client or do family members own any firearms? If so, ask them to keep them

secure when you are in the home.

4. Does the client or any family members participate in any sport or hobbies (as an element

of friendly conversation to help you forecast for the presence of possible dangers in the home)?

5. Please refrain from alcohol or drug use during the visit.

Note: while these safety expectations must be set, be sure to preserve the client’s dignity via your tone and other non-verbals.

iii. Evaluate responses-

- Did the client swear, shout, use disrespectful language, or display any verbal Gateway Behaviors during the call? If so, were you able to persuade them to stop using? (see the detailed description of the Persuasion Sequence later in this manual)

- Did the client make any implied or overt threats?

- Did the client refuse to cooperate when asked to secure pets or weapons?

- Did the client refuse to cooperate with scheduling a visit or cooperate with any other objective connected with the call?

- If you met the client previously in court or at the organization, did they exhibit any Gateway Behaviors?

Developing a Safety Plan

Document and report all pre-incident indicators for violence discovered in the initial telephone screening and take appropriate action according to your organization’s policies and procedures. If the client poses a risk based on their history and/or behavior or level of compliance during the initial phone call, court appearance, or office visit, develop a safety plan for the initial visit (scheduled or unannounced) according to your organization's policies and procedures.

Options for safety planning when risks are identified:

- Suspend the home visit, and if appropriate, ask the client to come to the office for the initial visit or hold an initial meeting at the courthouse or police station

- Schedule an initial visit with security or law enforcement support present

- Schedule an initial home visit with an organization partner or supervisor present

- Report concerns to the appropriate authorities before proceeding

Preparing Your Vehicle and Yourself

Once an initial visit has been scheduled and any safety planning required has been completed, you should prepare yourself and your vehicle for the visit.

Prepare your vehicle

- Equip your car so you are prepared for an emergency (e.g., battery cables, spare tire, flares, first aid kit).

- Sanitize your car for safety. There should be no visible clothing, packages, mail, bags, electronics/laptops/chargers, or money (even change in drink holders). When someone looks in your car, it should appear completely empty. If you need to place your computer bag, purse, jacket, or other valuables in the trunk, do this before arriving at the destination so others don’t see you do it.

- Make sure your vehicle is in good working order (starter, tires, battery, wipers, window operation, etc.).

- Make sure locks and remote are working properly.

- Make sure you have plenty of gasoline or electrical charge.

Prepare yourself

- Sanitize yourself for safety; meaning, take only the items you absolutely need with you into the home. These are the items you are willing to leave behind in an emergency. If possible, leave your coat or jacket locked in the trunk and wear a warm sweater or layers that will remain on your person during the entire visit. If you must take a jacket into the home, wear it during the entire visit and do not remove it. Anything you need should be stored in a pocket or a small bag that you can keep on your person at all times.

- Make sure your cell or satellite phone is completely charged and programmed with emergency numbers. Have a backup battery on hand. A working telephone is essential to your safety, even in areas where cell phone coverage is limited or non-existent.

- Keep your keys, professional identification, and phone on your body at all times, not in your jacket, bag, or portfolio. In the event that you must leave the home quickly, you will not have time to locate and retrieve your keys or phone. If you left them in a bag or jacket and you are separated from them, your options for escape and to call for help are immediately limited or lost. In the event that you do not have pockets in your pants/trousers, a light jacket that you keep on during the visit may provide storage for these items on your body. Clips on your waistband to secure your phone is another option. A spare key and remote on a lanyard are also recommended and can be worn inside your shirt or sweater.

- Ensure you have an organization identification card and your identification badge.

- Do not wear anything that can be easily grabbed (e.g., necklaces, chains, ties, long hair, dangling earrings).

- Do not wear or expose anything that may trigger negative reactions, such as a political button or religious jewelry. Also, cover tattoos or body piercings that may attract attention.

- Avoid wearing items that are, or could be perceived as, expensive or of having great value (e.g. name brand shoes, large stone jewelry, “flashy” watches, etc.).

- View a map of the area you will be traveling and make sure you have clear directions to each destination (preloaded into GPS device, printed out), so you never appear lost. Know where to park and know the routes you will take to leave. Identify the location of the local police station and businesses and check if they will be staffed/open during your visit times.

- Wear shoes and clothing that would easily allow you to run and fight if necessary.

Stay tuned for future blog posts to read parts 2, 3 and 4 from the Personal Safety for Home Visit Workers manual! Or for more information about how Vistelar can help you and your organization, contact us today.