“Empathy as a Strategy for Safety” - Episode 1

Host: Al Oelschlaeger

Guest: Dan Garris

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube.

Did your first job as a kid lay the groundwork for what you do today? Dan Garris, Workforce Development Trainer for Portland State University, reminisces about how his simple paper route prepared him for his critical interactions on the job today. Garris shares his personal experiences working in Child Protective Services and how “listening with five senses” prevented situations from escalating. People working in social services are faced daily with many issues such as substance abuse, poverty, and those struggling with mental health issues. How can practicing empathy prepare social services workers for these interactions? Garris breaks down the specific ways we can show empathy and respect as more than a value to live by but as a strategy to practice daily in our efforts to keep everyone safe.

To learn more about non-escalation, de-escalation, and personal protections visit vistelar.com

Allen Oelschlaeger: Good afternoon, Dan.

Dan Garris: Hello.

Allen: It’s great to have you on the podcast here, the Confidence in Conflict podcast. I understand you were a paper boy when you were a kid, is that right?

Dan: Yeah, I did a little bit of paper routing as a kid, and yeah.

Allen: I’d love to hear the story, because I didn’t have a paper route but I would sub every summer for somebody that had a paper route and so I’m curious as to what you’re going to tell us here about the paper route business.

Dan: Yeah, happy to tell you about it. About 10 years old when I … I actually helped and partnered on a paper route as well. I was not completely solo on this. But I like to tell this story about doing a paper route because I think that it was really my first introduction to dealing with the public and having to deal with some conflict along the way.

Dan: The reason I say that is because as a 10-year-old, one of the things you did as a paper route and maybe a lot of young folks out there may not remember what the old days looked like with papers, but you had to walk around door to door, in your neighborhood, or where your paper route was, and you had to do what they called collecting. What that meant was when you knocked on the door, you had to talk with people about re-prescribing or subscribing I should say to their paper.

Allen: Because I did the same thing, was that every month or every week you collected?

Dan: It was every month as I recall.

Allen: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I think so.

Dan: When I went into it, that is to say when I went into having to go door to door, I had some butterflies in my stomach about it because I knew that people could be cranky about it and other people would be kind about it and some people want to cancel their paper and some people want to argue. I was only 10, and thinking back on it, I believe that that was really my first introduction to having to deal with just all kinds of different ways that people express themselves and having to try to still sell that paper.

Allen: Yep. Well, I don’t know if you know. Do you know that I sold books door to door when I was in college?

Dan: I remember you talking about, yeah, doing that selling, selling door to door.

Allen: Exactly the same experience. I remember when I was in college, I talked to some career guy and he goes, whatever you end up doing in your career, have some job either it was … In his mind, it was two jobs. Either you’re a waiter or waitress, where you’re dealing with people obviously all during the entire time and you got cranky people and whatever like you’re describing, or do something door to door, book sales, paper route, whatever, that that would be great preparation for whatever career you’d end up having.

Dan: It certainly was preparation for the kind of career I eventually went into, I’ll say that much.

Allen: Exactly. That’s what you train people to do. You actually live in an area where I grew up, is in … What do you call that area? What’s the official name for it? Is it Salem, Oregon, but what’s the …

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: Willamette Valley is that what it’s called?

Dan: It’s the Willamette Valley. I live in Canby, Oregon with my family and that’s outside of the City of Portland, and they do call it the Willamette Valley because Willamette runs right through all of this area. In fact, on my way to work, I have to cross over the Willamette.

Allen: I know you moved there a little later. You grew up in California, but does anybody still talk, given that we just this Monday … Is it this Monday or last Monday? Columbus Day was? Oh yeah, this coming Monday is Columbus Day.

Dan: It’s coming up. Yeah.

Allen: Yeah. So does anybody talk about the Columbus Day storm?

Dan: I recall the Columbus Day storm as far as hearing about it, but no, I don’t hear a lot of people talking about it anymore.

Allen: I mean, this came up yesterday because I was in a Columbus Day storm. Turns out I was 10 years old. You’ve talked about being 10 years old. I was 10, lived in Lebanon, Oregon, which I think you know where that is. The storm, I don’t think was predicted at all, came through kind of Oregon. I think it hit Portland. I think it touched on Seattle a little bit but was primarily in Oregon. I just looked this up, Lebanon had 127 mile an hour winds.

Dan: 127, wow.

Allen: It is. I’m reading this from Wikipedia, the storm ranks among the most intense to strike the region since at least 1880. The storm is a contender for the title of the most powerful extra topical Cyclone recorded in the U.S. in the 20th century.

Dan: That’s amazing.

Allen: I lived through it, but we had eight trees on our property and five of them fell down that night. Yeah, windows breaking, but as you know, Oregon doesn’t get weather like that. We don’t get big storms.

Dan: No, it’s considered relatively mild throughout every season. However, I will say in the ’90s, and I can’t remember the exact date, there was the big three they called it. That was, we had flooding, then we had freezing and snow and ice. That’s more than three, but we get the picture. It was very treacherous because that was when the Willamette almost breached its walls in the Portland area and did in some areas Oregon City was just underwater in some places. And then after the floods subsided, the water started to freeze all over the place and nobody could go anywhere. It was a pretty big deal.

Allen: Dan, that sounds like every winter in Wisconsin.

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: Yeah, exactly. Okay, so let’s talk about, what do you do now door to door? You have a completely different job than doing a paper route.

Dan: That’s funny that you say door to door because that’s exactly part of a lot of what my career involved. Let me just say what I do right now and then how that relates to what I used to, because they’re very connected. What I do right now is I’m a trainer, a Workforce Development Trainer for Portland State University.

Dan: We call ourselves a partnership because we partner with the state of Oregon to train their child welfare, and other kinds of state employees, their basic training, their academy training, and we also do their advanced training for them too. What that involves is a huge array of different training topics.

Allen: Dan, just to make sure everybody that’s listening understand, child welfare.

Dan: Yes.

Allen: I think in other states, it’s called Child Protective Services or Family Protective Services, but just describe what that means.

Dan: Sure. Child welfare or human services or any of the things that you just mentioned, Family Services as it could be called in a lot of different states, is that part of the government, state government that does child abuse or child maltreatment investigations and then subsequently works with the family to try to create better outcomes for the family so that they can function a little bit better than we found them when we first found them.

Dan: Some of the things that child welfare typically investigates are some of the most entrenched social problems that we have out there, including mental health issues, substance abuse, criminality, poverty, and a lot of issues that people really struggle with, then they bump up against the child welfare system because they’re having trouble taking care of their kids or they’re actually doing something that’s against the law regarding their kids. There’s a real investigative element to child welfare, and then there’s family services element to it as well.

Allen: How many child welfare workers would there be in Oregon?

Dan: In our child welfare agency in Oregon, we have a little over 2,000.

Allen: Wow, wow.

Dan: And then in DHS, the Department of Human Services, which umbrellas many human services activities, there’s about 8,000 employees.

Allen: Wow.

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: Those kind of numbers would be pretty state by state kind of population based would be about the same, you think?

Dan: I would imagine they probably are. Yeah, because they’re trying to staff caseworkers to the populations that we work in.

Allen: So obviously, this is much more serious than collecting money on a paper route. So, you’re a trainer and then you’re going to go back talk about what you did prior then.

Dan: I’ll just jump right to the door to door part of it. When I first started out in child welfare, I was a caseworker and then within a couple of years, I moved to child abuse investigations. There’s different kinds of units and different types of case work. So I did investigations for several years, and then I became a field trainer, which was more of a consultant.

Dan: I’d go out with the caseworkers and go door to door with them and teach them how to deal with the challenges and the resistance and the difficulties people were having in order to get the job done, basically, so that they could actually talk to the family and figure out what was going on. Then I became a child welfare, or a child protective services supervisor, and I supervised those folks for several years before I became a trainer for Portland State University. That’s kind of my trajectory in a nutshell.

Allen: So you effectively worked for the state for all those other years and then switched to work for the Portland State.

Dan: For the partnership, which yeah, it’s located within the School of Social Work and they have a partnership to train all of their staff in the state.

Allen: As we do on this podcast, we try to better understand how to deal with conflict. Obviously, you as a supervisor, your employees, and now as a trainer dealing with people, they’re dealing with a lot of conflict. So this is kind of the extreme. It’s like every day, I can’t imagine. I mean, it’s probably pretty rare that you’ll walk in and knock on the door and have it not have some conflict.

Dan: Well, I think the norm is that you’re working with people who are not asking for your help. They’re not voluntary. They’re involuntary, right?

Allen: Yep.

Dan: So, right from the get-go, you’re having to manage people’s questions and people’s anger and frustration and a lot of resistance.

Allen: I know you have a story that I’ve heard before, but why don’t you take us through that story and just highlight some of the methods you use to deal with conflict when it comes up? As we’ve discussed, [inaudible 00:12:00] I mean, so the goal here is how do you better manage conflicts so that one, things don’t escalate and if they do escalate, you get them settled down rather than things turning into a nightmare.

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: Yeah.

Dan: I’d love to tell the story. I told the story before to groups that I trained so that they can get a sense of I guess the fear and trepidation that anybody naturally feels knocking on somebody else’s door. Because one of the things I like to talk about before I even get to the door story is that when you cross the threshold of somebody’s door, we ought to be treating that as sacred territory. That’s a family even if they’re struggling, even if they’re having a really difficult time.

Dan: That’s part of the nervousness that I always carried with me is that I was entering into something that was really important not just for me, but for them, whatever their situation was. So I like to try to figure out a lot of stories that have to do with that. This story that I’m going to tell is one of those stories. The person involved was difficult, but in a way that was unusually difficult for the kind of difficulty that we normally experience, which is more boisterous. This was very much less boisterous.

Dan: So, let me begin the story. I was a fairly brand new caseworker, or investigator. The way it works is that when you get a case, if it’s been a case that people have worked before in your office, usually people are going to come up to you and tell you a story about that case, or how it’s going to go or how the person is going to be or whether you’re going to be able to work with that person or not. So this was one of those kinds of situations.

Dan: This family had upwards of 20 to 30 prior referrals already, and so that’s quite a lot. That’s unusual. That’s an unusual amount of referrals. Referrals meaning reports that come into a child abuse hotline that other investigators had gone out on before, or that had just been screened at the hotline and closed. So when I got this one, I hadn’t really been out on very many cases, but I had been out with …

Dan: Typically we go out with another case worker, or we might go out with a police officer to a situation, so I’d already had those kinds of experiences. So I knew what people had done before me. What worked, what didn’t work, what seemed effective or didn’t seem effective. The first thing that happened when I got this assignment is that people, a couple of people came up to me and let me know that this was the worst house they had ever seen.

Allen: Oh wow.

Dan: As far as neglect and trash and clutter. And then the second thing I heard was you’re not going to be able to work with this person because they don’t like to open the door and let you in. That’s kind of the preparation I had going into this situation.

Allen: Dan, just so we understand, so you’re in an office and you get an assignment where … How do you get that assignment? Is that just a phone call or a piece of paper that comes? How do you know you’re going to go to this person’s house?

Dan: That’s a great question. What happens is, we have a screening, a child abuse hotline, as they call it. A child abuse hotline is separate from what child abuse investigators do. We’re in units that are located within the community. The child abuse hotline is a screening hotline that takes all the calls from the community. So that’s how it happens. Somebody calls in, a concerned citizen, a police officer, a school counselor, a family member, it can be a variety of people who have eyes on in the community and they see something happening and they’re worried about it, so they call in.

Dan: The screener decides whether it meets the criteria for an investigation. And then once they decide, yes, this is assignable, they send it to a CPS supervisor or Child Protective Service supervisor. That supervisor then looks at who’s up on rotation for an assignment. They say, “Dan, here, take this.” They’ll sit down with you for a second and maybe talk about the case for a moment, and then send you on your way. Then you go out.

Allen: What do you have? Do you have a transcript from the phone call or just some notes, or is there a case file on this household?

Dan: Yes. There’s lots of sort of information systems that we can check, and do check. The first is just a piece of paper that you get, which gives the narrative of what the concerns are and gives some demographic information on the family. It’ll list the number of prior referrals. It’ll also give a notation of how those referrals were labeled, whether it was neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, threat of harm is another category.

Dan: So it’ll list that and then we have electronic systems that we can go and read some of those old rules. And we also have LEDS checks that we can have done for us by LEDS operators, so we can look at criminal history as well before we go out.

Allen: Is that like a five minute review or a hour review? How much time are you spending before you actually head out on the assignment?

Dan: I would say that once you sort of know the ropes and know the systems and who to talk to, it shouldn’t take you more than half hour to collect all that information. You’re not supposed to do an exhaustive investigation before you go out, but you are supposed to do some preparation before you go out. That is the preparation.

Allen: Okay.

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: So you’ve got the hour.

Dan: Yep.

Allen: And you’ve heard these stories, and then you get in your car and you’re driving to the house.

Dan: That’s exactly right, drive up to the house, and sort of sweating all the way from what I’ve heard so far. This one, I went out by myself, I didn’t have anybody with me. I drove right up to the front of the house. Now, in hindsight, I’ve learned when I was doing the job that that wasn’t a very good idea to just drive right up to the front of the house.

Dan: I know law enforcement and child welfare do things completely differently. I would thereafter like to park down the street a little bit, so that there wasn’t a state car right out there in front so that people could see that and get panicked right away and start the exchange that way. But this time I did. I parked right out in front. And then as I got out …

Allen: Dan, just a few weeks ago, I had a chance to talk to some child welfare folks here in Wisconsin and they told us a story about how they learned that lesson where they parked in front of the house, and they got boxed in by like some friends of the person from the house. They learned their lesson never to, like pull into a driveway. It’s pretty easy to box somebody in. So you park down the street, you make sure you’re in a position where your car can leave without having somebody get in front of you. Yeah, so a lesson well learned. Yeah.

Dan: Very interesting that you brought that up because it kind of reminds me of going into apartment complexes where the residents knew child welfare really well because we’d be out there all the time. You’d pull up and sometimes you had a friendly response.

Dan: But you’d have these self-appointed neighborhood watch people come up to you and want to talk to you and ask what’s going on, and what’s the trouble today and all those sorts of things, but sometimes you had the people who are not as friendly come up to your window and say what are you doing here and all those things. So, I totally understand those other folks that you were talking to about how they’d like to park somewhere else so they can avoid some of that stuff.

Allen: Exactly.

Dan: But I didn’t learn that lesson early on. I was out there right there in front of the house. And as I looked at the house, it was a house. It wasn’t an apartment. It was just a single dwelling type of a house. There were black garbage bags just lined up on both sides of the house and already that kind of put a pit in my stomach and I was thinking, oh my goodness, this is going to be bad. It’s not going to be good.

Dan: So I was already kind of spiraling into a negative mindset about how things were going to turn out. So I got out and I walked up to the house. The other thing that struck me right away, first was the garbage bags. The second was the odor. I know Allen, as you’ve talked to some of your child welfare friends, they’ll tell you about odors. They’ll tell you that.

Allen: Yep. Yep.

Dan: That goes for any contact professional or person who knocks on people’s doors, whether it’s law enforcement, the Fire Department, healthcare worker.

Allen: Book salesperson.

Dan: There you go. Absolutely. Totally.

Allen: Yeah.

Dan: So that was two things struck me right away. I hadn’t really smelled anything that strong before in my career. As I said, I was fairly new at this point, so I was pretty on my heels at that point. So the next thing I do is I knock on the door, and I’m trying to think of what I’m going to say. At this point, I’m not really very polished in my introductions. I’ve heard what people have said before, like I said before, as far as things that sounded good, things didn’t sound so good, didn’t work so well.

Dan: I was thinking about what I wanted to say. I was also thinking about what I had been told in the office that the person wasn’t going to answer the door. But the person did answer the door. And that’s kind of where the story begins. When the person answered the door, they only opened it up about an inch and a half. So there was a crack in the door, and that was it. Through that crack in the door, I could see this person’s eyeball staring out at me, and so I thought that was my cue.

Dan: So I introduced myself, “Hi, I am Dan Garris. I’m from child welfare, and I’m here because I got a report about some troubles you may be having, and I’d like to come in and talk to you about that.” No response whatsoever. Just I expected a response. I expected maybe a boisterous sort of an upset response. But I didn’t expect total silence.

Dan: That silence seemed to last for decades. So I’m waiting and now I’m looking at her with my one eye and she’s looking at me with her one eye. I tried again to introduce myself, kind of repeating myself and nothing. At that point, I remember distinctly kind of reeling through different options of what I’d seen people do before. Now, I say this sort of in a humorous way, but it actually happened. I remember going out with a police officer one time in a different situation, and as soon as that crack in the door happened, a big black boot went into that crack in the door. And that’s how we got into that house.

Dan: I’m thinking I don’t do that. I better not do that. That’s not going to work. And then I also remembered just some of my coworkers doing what I call an either/or shtick, either you let me in or we’re going to call the police or some bad thing is going to happen. I thought, I don’t really want to do it that way. I’ve never really seen that work very well.

Dan: I want to step back for a second and say something about that police officer experience. As a Child Protective Services investigator, I just want to say that most of the police officers that I’ve worked with have had just stellar communication skills and I’ve learned so much from them over time. There’s always a few who are not quite as polished, whether that’s child welfare, whether that’s law enforcement or whatever the profession is, but I didn’t want to give that one example as a paradigm for my experience, because most of my experience with law enforcement has been a learning experience really.

Allen: Well, and it’s a universal. As you know, we deal with law enforcement quite a bit. The guys that are good, there’s nobody better in terms of communications. I mean, the old timers have been out there for 20 years, they’ve learned through the school of hard knocks, I mean, they know exactly how to deal with these situations in a way that you just go wow, that was amazing.

Dan: Absolutely, absolutely. So I reel through those scenarios in my mind, and I just dismissed all of them and then I don’t know if it was sort of an epiphany or what it was, but something came to mind. I can’t pat myself on the back for this, call it providence, call it the universe, call it whatever it was, but something just came to me to say, because again, I don’t really feel like I have the toolkit back in those days to draw on the right tool for the right job.

Dan: I waited for heaven to open up. In this case, it kind of did. And it wasn’t very profound, but it came out in a way that made a difference. What happened was as she stared at me, I said, “Things must have gone on in your life that haven’t been too good, that has been pretty bad for you to get us to this point in time right now where two people are just looking at each other through a crack in the door.”

Dan: At this point, at this time, my pause was strategic. I remember that much. I waited for her response. That’s what I mean by strategic. I just waited and I thought I was going to get the dead blank stare. But I noticed something in that eyeball change. It’s hard to describe it except with the word soften, it seemed to soften.

Dan: That eyeball softened and then what followed was a black tear of mascara running down her cheek, and I guess that’s sort of an indelible mark on me now because I see that mascara running down her face through that crack in the door. I still see that two inch crack and that black mascara just running down that crack in the door. That’s an image that I’ll never forget.

Allen: Yep, yep.

Dan: And then the next stuff sort of just felt like it came naturally upon that experience. And the next thing I said was, “I know it’s going to be really bad in there.” I used an if statement, but it wasn’t a coercive if statement. I said, “If you let me in, we will work together. I don’t know how it’s going to turn out. But we’ll work together. That much I can guarantee you, and we’ll work something out. Whatever it is.”

Dan: And then the door slowly opened, and I went in, and it was terrible in so many ways. It’s really not the point of the story to tell how terrible that was. But it was terrible. I remember that was the beginning of probably nine to 10 months of working with this family to try to resolve some of the issues.

Dan: Back in those days of Child Protective Services, sometimes we were able to keep cases a little bit longer. In modern terms of child welfare, the CPS worker just does an initial investigation and then moves it along to a family services worker pretty quickly. But in this case, I worked with this lady for quite a long time. Anyway, that story taught me so much, Allen, about myself.

Allen: Yeah, so it’s all right. Just hit some high points there and things that we teach at Vistelar. So yeah, why don’t you highlight some of the things you did there that now are probably part of your toolkit and I’m sure you teach people. So yeah.

Dan: I think what’s great about recalling the stories of our experiences is that we can be honest about the fact that we weren’t great or we weren’t good sometimes or we weren’t the best, but we can retrofit some of the skills that we’ve learned. I’ve learned communication skills from a lot of different sources, one of which is Vistelar, and I can really retrofit the story to a couple of things.

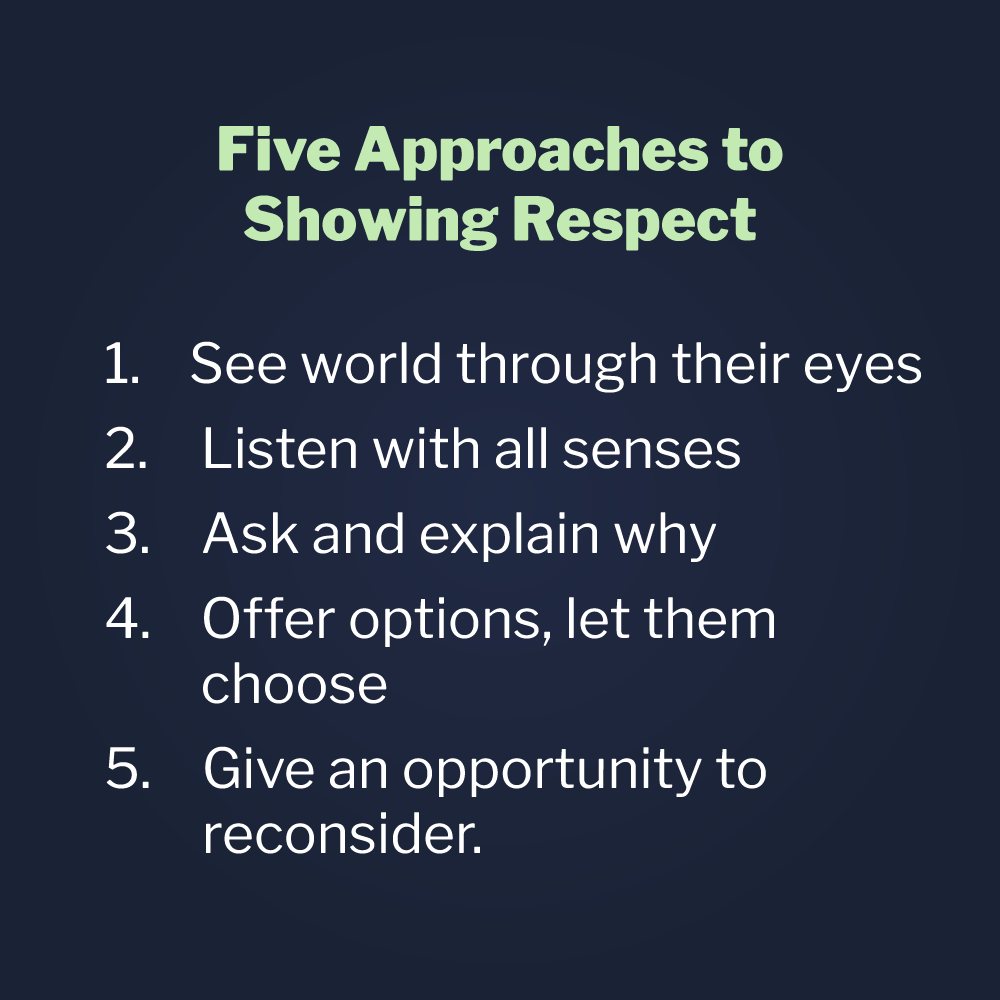

Five Approaches to Showing Respect

Dan: One would be Vistelar’s core principle, and I’ll say what that is, and then the second would be relating it to the five approaches that Vistelar talks about, which are the five ways of actually tangibly showing respect to people in those kinds of situations. So, I’ve been able to retrofit that, because that experience touched upon all of those things.

the five approaches that Vistelar talks about, which are the five ways of actually tangibly showing respect to people in those kinds of situations. So, I’ve been able to retrofit that, because that experience touched upon all of those things.

Dan: And the first being the core principle, which is to treat people with respect by, underline by, showing them respect. Treat people with dignity by showing them respect. I know that Vistelar says even when we disagree, and I agree with that statement, but what I like to say in training is treat people with dignity by showing them respect in five distinctive ways.

Allen: Yeah, there we go. Yep, love it.

Dan: The reason I say that is because in child welfare, clichés like in any profession get thrown around, like we need to respect people, or people deserve dignity and respect, and that’s the and, underline and. That waters everything down. It doesn’t really say a lot. It just sort of expresses the value, which is a good value, but it doesn’t say a lot.

Dan: But when we talk about treating people with dignity by showing them respect, in five distinctive ways, now we’re talking about something that may be actually practical and useful. That’s the core principle that I’ll retrofit here. And then the five distinctive ways is what I think I can go through. The first of the five …

Allen: Dan, just one comment because you did a … One thing that, if you’re dealing with a neighbor or a family member, or whatever, and I’m sure you’re going to talk about empathy, which is a big aspect of all this. It’s so easy, well it’s not easy sometimes, but you know these people, they’re friends or they’re family and to treat them with respect is something that using that terminology is something that’s doable, right?

Allen: In this case, if you’re a police officer and you’re dealing with a criminal, in this case, you’re dealing with somebody that’s obviously we don’t know the details but obviously some struggles with their family. I did some work with utilities people to go out and have to go and do a door to door thing where people that are stealing energy from the utility companies where they rewire their energy meter, right?

Dan: Yeah.

Allen: It’s hard to walk up to the door and have respect for that person, right? Because they obviously are doing some things wrong, but you can certainly still show them respect. That’s the key message here is, you’re treating them with dignity but you’re showing them respect and you’re doing that because it works, and your story is a prime example of it.

Dan: Yeah, I’m glad you brought that up, Allen, because that is exactly the distinction that I feel like at least my trainees, and I know other trainees need to hear because it is difficult to just conceptualize respecting somebody who’s doing something that’s morally abhorrent in some cases. Like abusing their children, that’s morally abhorrent. We can’t really wrap our minds around how that person could ever earn our respect, and that’s a very valid point.

Dan: The showing of respect, though, is a behavior. It’s a strategy and a tactic that, as you said, works. But it also does some other things for us too. I think I’ll get into that a little bit later in the story what that actually does for us and the other person that we’re dealing with, to change the situation, to change ourselves.

Dan: So the five, the first of the five ways of actually showing respect is seeing through the eyes of that person. In this case, with the story that I just told, well, we’re dealing with an eye. So the eyes feature very heavily in this story.

Allen: Yep.

Dan: But I think, on a very serious note, seeing through that person’s eyes was something that came to me because I couldn’t bring myself to do the other things that were coercive. I was very fortunate. I don’t know why I was fortunate in that way. But I was very fortunate to stumble onto the ability to see life through her eyes by recounting that idea that things must have gotten pretty tough for her and pretty bad for her for a very long time to get us to a point of two people looking at each other through a door.

Allen: It’s probably, Dan, the first time she’d heard that for years, right? Something where somebody was coming across with some empathy.

Dan: I would imagine that you’re right about that, that that might have been the first time, because I didn’t hear everybody’s story in the office, but I heard a couple of stories that that lady’s not going to open the door for you.

Allen: Right, exactly. Yep. Yep. Tears don’t start flowing if it’s just clear. I mean, just when you’re listening, [inaudible 00:35:33] they’re going on, wow. Yeah, exactly. She’s sitting there. She’s going, okay. This is the first person that’s ever come to my door and never seemed to have some understanding of what I’ve been going through here.

Dan: Yeah, and that’s something that we can … That’s a skill that we can develop. That’s why I really appreciate the five skills, the five ways of showing respect, the first of which is a listening technique of seeing through somebody else’s eyes. That requires not an absolute knowledge of somebody’s history, but the ability to listen to what’s actually going on.

Dan: Now, this was all nonverbal, so I wasn’t able to use the listening technique of reflecting back what she was saying to me. I had to make a big guess here, and I guessed relatively well. Something struck a human chord in her, and so that’s the first one, mission accomplished. I was able to see life through her eyes a little bit and reflect that back to her in those words.

Allen: Yeah.

Dan: The second one is listening with all of your senses. I think this one’s hard to wrap our minds around, but in this case, I think this story illustrates listening with all of your senses because I was experiencing a lot through my senses. I was smelling a lot of bad smells, and when I thought about it, I could smell the way that she was living, and that was tragic. I could understand that as a human tragedy, not just for her, but especially for the children that were living inside that house and for her.

Dan: Like you mentioned too, she has a family too, she has an extended family. So this has got to be painful all around really for people to see all this. It’s hard to start there. It’s easier to start with disgust than it is to start with that kind of a thought. But some of those things occurred to me as I was smelling the situation. But also the other thing, the biggest part of listening with all of your senses in this particular context, was seeing the change in that eyeball. That was the thing that, like I said, I’ll never forget that.

Dan: If I hadn’t been paying attention to that to see that, the next step might not have happened. Which was the step of being able to get into the house and talk with that person. So listening with all your senses is not just the words that we use, or the way that we listen, it’s really watching and seeing what’s happening with another individual, making observations around us about how that person may be living and what the implications of that life could be for them, and making an effort to connect with that in some way.

Dan: It doesn’t have to be super profound. It just has to be those short words that I shared with you before. So listening with all your senses. The other thing that I would say about that, just in terms of this story was, we also have to watch for people’s flight, fright, and freeze responses. She was probably frozen with fear for a period of time. Now that changed. That changed in that context from being frightened and being frozen to being cooperative on some level.

Dan: But we have to watch for that too, and empathize with that experience rather than label it something else. What I mean by that, it’s easy to label those experiences as something else, like manipulative, uncooperative, difficult. There’s all kinds of labels we can give to that kind of an experience. But when we do, we’re really just listening to our own biases. We’re not listening with all of our senses at that point.

Allen: Yep.

Dan: So the third one is ask and explain in the five ways of showing respect. I didn’t do anything revolutionary here in this situation, but as soon as I had an opportunity and the opportunity came when I saw the tear running down the cheek. But as soon as I had that opportunity, I started to explain a little bit more about what was going to happen next. What’s important about that, I think, and how we can kind of look at these five for a lot of different situations is that it’s easy to be coercive.

Dan: It’s easy to tell people what to do. It’s easy to say, if you don’t do this, then this is going to happen. Those things come naturally to us. I think they come naturally, because when we’re under pressure, we just default to that kind of an expedient. Now, if you don’t do this, then this is going to happen, and you got to do this or else.

Allen: Dan, it was on TV just a few weeks ago where a newscaster wanted to have the experience. I don’t know if you’ve ever been inside of one of these simulators, where they have a little scene going on and then you have to react to the scene, have you ever done that?

Dan: Way back in driver’s education school.

Allen: Oh, there we go. Yeah, I think those were the original ones were driver things, but now there’s actually 360 degree or 300 degree rooms you can walk into and they have a scene and then there’s an operator running this little contraption and then you’re responding to the scene and then the operator can take the scene in various branches based on how you respond. So the newscaster without any training goes in and is faced with all this very stuff, I won’t go into details.

Allen: But just like you’re describing, I mean it was all the natural stuff. He’s doing everything wrong, just everything. He gets out, gets back on the show going, “Yeah, I had no idea what to say. I had no idea what to do in this situation.” If you do what kind of comes naturally or maybe what you saw in her, whatever your life’s experience was with TV or movies or your family or whatever, yeah, you’re probably going to end up not doing it right.

Dan: Totally agree with that, Allen. Yeah, I mean, when you see somebody kind of struggling and going into that natural mode of reacting to people, it’s very easy to see how that ain’t going to work. Just making the situation worse.

Allen: And you knew that this … I mean, this guy was a newscaster, smart guy and you could just tell that when he got back on the show he goes, “Wow, I didn’t handle that very well.” It was pretty obvious to him that he didn’t do it right, didn’t do it well, things got worse, but he had no idea how to do it right.

Dan: It can absolutely happen to the best of us. But you hit the nail on the head, I mean, a person who’s skillful in communication, different communications techniques can get it wrong sometimes. Nobody’s perfect. But the person who has no idea what to do whatsoever is really out there in no man’s land, so to speak, right?

Allen: Right.

Dan: So, yeah, I appreciate that comment. So ask and explain why. And again, it wasn’t revolutionary. It was just taking the opportunity to really explain a little bit more about what was going to happen next. That was the thing that preceded the door opening is giving her a little bit more information.

Dan: And then the fourth one down is offering options to people, letting them have an ability to choose even under circumstances that are very powerless. I could very easily see how, and you mentioned this before, Allen, that her experiences in the past probably weren’t very positive with professionals perhaps. But it’s very easy to take a powerless person, and a person who really has very little latitude to make any choices in a situation like that and make him even more powerless. It’s not hard to do. It’s pretty easy.

Allen: But that power of a choice is such a big deal. The choices don’t have to be big choices. In this case, her day was probably things getting thrown at her all day long and didn’t have a chance to make any choices for her life. I don’t know if I told you the story, but a couple of years ago I was in the hospital, you’re in bed, you’re completely subservient to anything that’s going on. I remember just how satisfying it was when the nurse would come up and say, “Okay, we’re going to take some blood. Do you want to use your index finger or your middle finger?” Oh, wow, I get to choose something. How great is that? Yeah, anyway.

Dan: Hopefully you didn’t give her your middle finger.

Allen: Right, exactly.

Dan: But as you said, Allen, the choices don’t have to be … It doesn’t have to be a laundry list of choices. In this case, it was just the chance to work together. I remember using the words work together, we can work together on this. That was the choice, and she accepted it. She accepted the choice.

Dan: The last one there is giving an opportunity to reconsider. In this case, I love this last one for this story, because we both, the lady with the black mascara tear and me, we both had the chance to reconsider. I got to reconsider the approach that I used with her because I was just about to use some other approaches just because I didn’t know what to do, that would not have worked. It would have been the same old story. It would have been another referral, another lack of cooperation story.

Dan: But in this case, I reconsidered and fortunately for me, something came to me in that human moment that made a difference, that touched upon these four that I’ve talked about so far. She had a chance to reconsider too. Obviously, the whole story represents a reconsidering of her position. It wasn’t really a position.

Dan: I think she was reconsidering her fear and her anxiety and she was reconsidering her level of trust for a stranger and a professional. That’s really, to me, why this story really resonates I think for me, and I hope for other people too, in how it actually represents both the core principle of treating people with dignity and the actual operationalizing of respect in those five ways.

Allen: But as you know, Dan, in our training, and the training you do out there in Oregon, I mean, you try to simplify this for folks, and we get it down to just five things here and a couple of tactics there and whatever. But inside, it’s not easy. I mean, this is still hard work right to … Like when you’re describing listening, and oh, just listen, but people think about their own lives and how they listen to others.

Allen: It’s frequently are you really listening, even with your ears, you’re saying, and we talked about with all your senses, which is even more of a challenge, but what’s going on in your brain is you’re waiting to interrupt that person, right? I’m sure you’re at the door going, what am I going to say next, and whatever? That stuff, it just naturally pops into your head and instead you got to just truly listen to the person. And obviously you did and she saw that. I think just you with that little eye going through the crack in the door, she saw that you were listening, and you had some empathy for her situation.

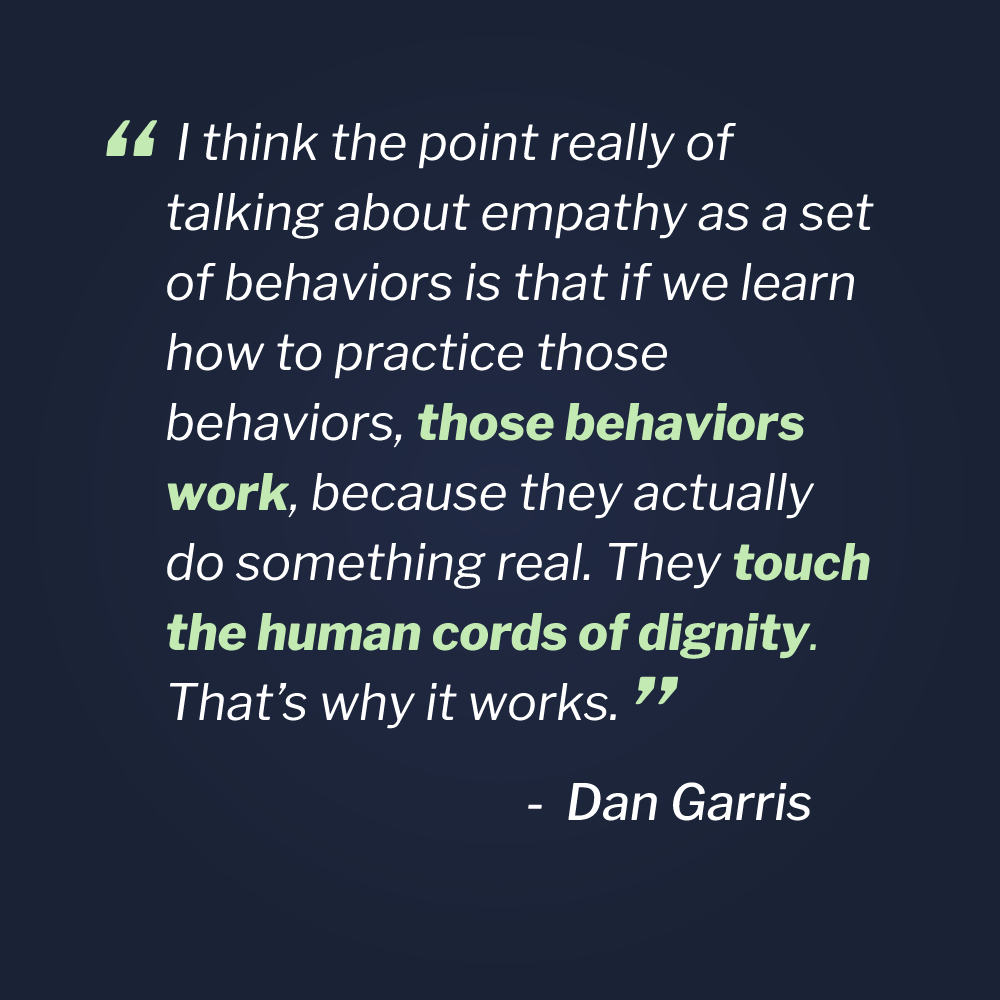

Empathy as a Strategy for Safety

Dan: Yeah. I think that raises the question of what empathy is and how hard it has to be. I don’t think it has to be as hard as we make it if we think of it as a set of behaviors that we’ve learned how to practice well. Whenever I say that, I always feel a cautionary twinge inside of me too. And that is, that caution is, I don’t want to sound like empathy is just a matter of robotically enacting certain behaviors and manipulating believers, so that you get people to do what you want them to do.

Dan: I think the point really of talking about empathy as a set of behaviors is that if we learn how to practice those behaviors, those behaviors work, because they actually do something real. They touch the human cords of dignity. That’s why it works. But the other thing that happens and it’s a bonus I mean, it’s not a necessary thing is that I think it changes us a little bit too. There’s an old word that I like to bring up every once in a while and that word magnanimous, you don’t hear that word very often anymore.

those behaviors, those behaviors work, because they actually do something real. They touch the human cords of dignity. That’s why it works. But the other thing that happens and it’s a bonus I mean, it’s not a necessary thing is that I think it changes us a little bit too. There’s an old word that I like to bring up every once in a while and that word magnanimous, you don’t hear that word very often anymore.

Allen: No, no.

Dan: But I think it makes us more magnanimous. I did the easy work of going back and looking at some of the definitions for that old word, and it’s very plain. It means large-souled or big-hearted or great-hearted.

Allen: Oh, wow. As you know, Dan, we’ve gone back and forth in some writing stuff and you’re a lot like me, right? In that that’s exactly what I was going to do right after this call is to go look that word up and see what it actually means, because I don’t … Yeah, obviously I’ve heard it before, I don’t think I’ve ever used it. You have some sense of what it’s about, but you don’t hear it enough to really put it in context. So very, very interesting.

Dan: I just think it makes us bigger to practice respect in those ways that we’re talking about, or empathy in the way that we talk about it at Vistelar, which are those three areas which overlay the five ways. The first in the empathy triad, of course, is acknowledging another person’s perspective. The second is really seeking a deeper understanding of what you’re experiencing with that person, and anticipating their needs. All of those are behaviors.

Allen: Yep. And you did that in 10, 15 seconds, as you were going through being at the door and the eye pokes out, that’s exactly what you did. You went through all three of those pretty quickly, right? But she got it. It sounds like you had an impact on her life as a result, instead of it being just another failure.

Dan: Yeah, a failure for her but also a failure for us too as professionals, because I think we can have enough core experiences with people that it hardens us and it doesn’t make us magnanimous. It kind of makes us bitter and angry. I really feel like that is the other upshot of practicing in this way of operationalizing respect in these ways is that it protects us too from that big issue that we always talk about now in the helping professions, which is secondary traumatic stress, and trauma.

Dan: We experience that as professionals, because we experience what other people are experiencing as trauma. You get enough firsthand exposures to that kind of stuff, and if you’re not taking care of yourself, I think practicing empathy is taking care of yourself. Practicing respect is taking care of yourself too. It’s a self-serving act, isn’t it?

Allen: Yep, big time. As you know, and I’m sure you deal with it all the time with the folks you train is that … I just read a book about empathy. And it talked about the difference between emotional empathy and cognitive empathy. Cognitive empathy being much more what you’re describing, where there’s a set of intellectual methods to show the other person respect, right? You’ve talked through the five things, but it’s all wrapped around empathy.

Allen: The book described emotional empathy, where it’s actually I’m sure this whole mirroring neuron thing, where if somebody else is experiencing pain that you actually feel that same pain in the same part of your brain. For people in social work, I’m sure that burnout and what they call compassion fatigue is a problem. Because if you have that mirror neuron thing going on and you got that emotional empathy hitting you every day, dealing with that day after day after day is tough.

Dan: Yeah, you’re right. It’s a huge problem, not just in social work, but in healthcare and law enforcement.

Allen: Healthcare in general.

Dan: Yeah, it’s a huge problem. There are ways to deal with it, though.

Allen: Dan, obviously, you need to be back on. You have a wealth of experience. This has been great. Why don’t we schedule that for the next call and talk about how to deal with compassion fatigue, because you’ve had to deal with it personally. You’ve been a supervisor having to deal with employees that had it. Now you’re training people that are coming in, and I’m sure that’s a big topic of what people have to learn how to deal with.

Dan: I would love to have a conversation with you about that.

Allen: Yeah, that’d be very good. So I hope that you don’t end up having some weird storm coming in on Monday, and losing all your windows and trees. I think you know that I grew up in that area, obviously. We have a family reunion every couple of years and I was just out in Washington up in the North Cascades, but now we’re planning on being at the Oregon coast in September two years from now. So, down near a … We’ll talk more about this next time too, but if you’ve been to the Pronto Pup Restaurant down right along the Oregon coast, what’s the name of the, Rockaway, Rockaway.

Dan: I’ve been to Rockaway many times and I’m trying to remember if I saw that sign, but I don’t think I’ve been into that restaurant. Are you going?

Allen: You need to go. Yeah. I’ll tell that story next time about my dad and the Pronto Pup, and how my daughter and I were driving along the Oregon coast way there and I’m going, “Oh my God, there’s a Pronto Pup store,” and we had to go in and talk to the owner. And sure enough, they knew my dad from years and years ago. So there’s a long story there. But we’ll talk about that next time.

Dan: Love to hear it.

Allen: Yeah. So Dan, thanks so much. Appreciate your time. This is wonderful.

Dan: Thank you.

Allen: And enjoy the rest of your day, and we’ll talk again.

Dan: Appreciate the opportunity. Thanks, Allen.

Allen: Yeah.