Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 1

How Much Danger Am I In? Be Alert and Decisive

“Only human beings can look directly at something, have all the information they need to make an accurate prediction, perhaps even momentarily make the accurate prediction, and then say that it isn’t so.” -Gavin de Becker

Though it rarely occurs to anyone entering the healthcare field that they might experience high levels of conflict and violence, soon after beginning their clinical training providers are taught to accept a culture of violence. That’s because the culture of healthcare embraces the belief that violence is part of the job. From one certainly tragic point of view the people who embrace this notion are absolutely right. Violence is a day-to-day reality in healthcare.

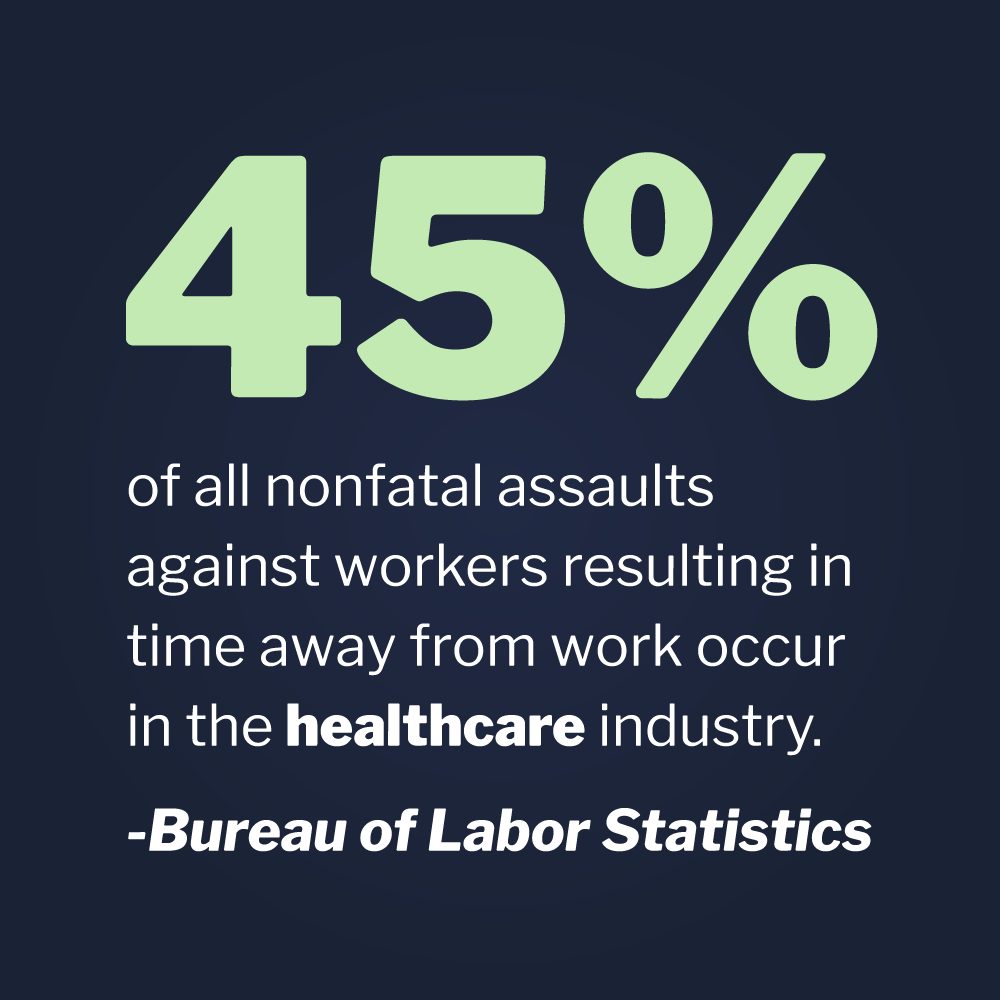

How bad is the problem? Among the ranks of risk management professionals workplace violence is a much talked about issue. But is workplace violence an even larger issue in healthcare? If the federal government’s own statistics from sources such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics are to be believed, healthcare is the most violent profession in the private sector. According the bureau 45% of all nonfatal assaults against workers resulting in time away from work occur in the healthcare industry.

talked about issue. But is workplace violence an even larger issue in healthcare? If the federal government’s own statistics from sources such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics are to be believed, healthcare is the most violent profession in the private sector. According the bureau 45% of all nonfatal assaults against workers resulting in time away from work occur in the healthcare industry.

OSHA estimates that there are approximately 2,600 non-fatal assaults on hospital staff annually. This estimate does not include homicides. Nurses, nursing assistants and hospital security officers are victimized the most, but no one in a hospital is immune. Everyone from physicians to pharmacists is assaulted on the job at higher than average rates. As one might expect, emergency medicine, critical care, and psychiatry top the list, but violence can and does happen anywhere in a hospital or clinic. In fact, hospital admissions and registration staff are also at elevated risk.

The levels of violence in healthcare is not going unnoticed by the CDC, OSHA, the Joint Commission and other agencies concerned with the health and well being of healthcare workers. In 2010, a Joint Commission Alert advised that healthcare workers need to take increased measures to curb the levels of violence in hospitals. Most significant perhaps is the alerts’ acknowledgement that violent crime is increasing in the healthcare setting and that workers, patients, and visitors are all at increased risk.

One of the more prevalent misperceptions is that these grim statistics, particularly those sourced from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, include numbers of minor assaults, such as shoves or spitting incidents. Nothing could be further from the truth. In order to qualify for the government’s statistics, workers must have suffered enough of an injury to miss time from work. We can place these numbers into an even clearer perspective by accepting the following reality. None of these statistics represent all of the so called “minor” assaults, such as slaps, shoves, unwanted sexual touching, spitting, verbal threats, and other assaults that do not result in time off from work. This represents an even greater number of uncounted assaults, because healthcare workers are notorious for accepting and under-reporting violent incidents. Police officers and prison guards are not so forgiving and rightly so.

In their groundbreaking surveys between 2009 and 2012, the Emergency Nurses Association discovered that half of all emergency department nurses surveyed have been the target of violence and threats on the job. Also, half of those who reported said they had experienced twenty or more violent and/or threatening incidents during their last three years on the job. Overall, even according to the government’s statistics, which are limited to assaults resulting in injury, around 20,000 registered nurses are assaulted annually and over 40,000 nursing assistants! Physicians, respiratory therapists, hospital security officers, x-ray technicians, social workers, and many others are also assaulted at unusually high rates.

The loss of quality healthcare workers due to violence related turnover and the hundreds of millions of dollars lost annually from injuries are devastating. In a very real way violence in healthcare has become one of the medical profession’s biggest problems and can no longer be contained as one of its dirty little secrets.

The following story is a blatant example — albeit an all too familiar one — of a level of acceptance that is perhaps unique to healthcare. While merely engaged in a casual conversation, a law enforcement professional asked a healthcare professional how her day was going. She related that moments earlier she had almost been sexually assaulted. This nurse practitioner was able to escape from the situation by having done an appropriate assessment and using some evasive tactics.

After escaping the potentially catastrophic attack, she told the shocked police officer that the police were not contacted and that she simply went to a location where others were present and waited for her attacker to leave the scene. She did say that she notified her supervisor and documented the incident in the patient’s medical record. The scariest part of the whole interaction was that, not only didn’t she feel the need or the right to access the criminal justice system, but that she did, in fact, report the incident to her employer and no law enforcement action was deemed necessary.

To make things even worse, due to a general misunderstanding of HIPAA and other laws governing patient confidentiality, she did not feel that she was able to notify the police. She also told the officer that all her previous training as a nurse caused her to accept that “these things just happen” and that they must be accepted as “part of the job”. She also believed that, if she were to pursue an investigation of the incident, it was quite possible she would lose her job.

In her interpretation of her role as a provider, she believed there was actually no recourse for her as a victim. In her mind her position as a provider denied her access to the criminal justice system and even a reasonable expectation of safety. There was no system in place, set by the employer, to protect her from any future occurrence. Instead, there was a professional culture to protect the offender from prosecution. Obviously, the environment of care in which she was working was compatible with violence; furthermore, her acceptance of risk for violent behavior was an expectation of employment. Is that reasonable?

Reasonable Expectation

Before we even begin to consider our rights under the law, our beliefs should always be subjected to the smell test of reasonable expectation. It’s time to ask ourselves, would she have adopted the above belief system if she were a waitress or a police officer? The answer seems obvious, doesn’t it? Then why is it okay to sexually assault a healthcare provider? If she asked a peer or her boss, if this was an acceptable risk, perhaps they might have answered yes. But, what if she asked her mother or her husband? What would any of their perceptions have been? In all likelihood they wouldn’t have been as accepting as someone who works in the healthcare field.

This scenario and many like it also begs the question, what if her attacker had just been a visitor or a relative of her patient? What if he had been a fellow employee or just some courier delivering a package to the clinic? The relationship between patient and provider is special, but is culpability for violent behavior really just a matter of context? Do any solid lines exist that no one may cross in the patient-provider relationship? That blurry line is at the heart of the problem of violence in healthcare. Providers cannot begin to protect themselves from violence in their profession, if they first cannot agree that they are entitled to their own personal safety and basic human dignity.

Another issue that combines to create a violent culture in healthcare is a lack of basic assessment skills. Though providers are adept at assessing their patient’s medical needs, they are generally poor at recognizing the cycle of violence. When we drive a car we look ahead, to the sides and occasionally behind us. We listen, we interpret traffic patterns, we look for danger, and we plan how to extract ourselves from danger. We also think about what measures we might take should danger spontaneously present itself.

Healthcare workers are an entirely different animal. Because they see so many sick and injured people, including many in crisis, they are desensitized to violence. Also, in order to function, they have to work comfortably inside what we normally view as personal space. Because they see us naked, jam needles in us, touch us in very private places, and see people often in varying states of fear and pain, they begin to disregard the pre-attack indicators of violence.

Applying the Concept of Isolation

Everyone in a hospital is familiar with the concept of isolation. In order to keep themselves and their patients safe from infection, providers utilize different layers of personal protective gear, facilities, and procedures depending on the situation. For example, if the patient presents with a respiratory infection, the first layers of personal protection are a facemask, gloves, and gown. If more serious infections are suspected, negative pressure isolation rooms, goggles, and other measures are introduced. In this present age of Ebola and MERS, full isolation suits, Tyvek “space suits”, filtered air ventilators and even SCBA (self-contained breathing apparatus) may be called for.

It all begins with an assessment. An assessment that answers this question: “How much danger am I in?” What healthcare workers have to begin to embrace is the notion of “forensic isolation.” That’s because providers are far more frequently hurt or killed by violent patients and visitors than they are by infections resulting from patient care.

Partly due to the extremely large levels of violence experienced by healthcare workers, an entire mythology concerning violence has taken root in the field of medicine. Healthcare has developed a culture of denial — a culture that dismisses threatening and even violent behavior. Healthcare has become, with all well-meaning intentions, a culture that has failed to understand the negative impact of anti-social, uncooperative, threatening, and violent behavior. It is a culture that also fails to understand the influence of unfettered violence on the outcomes of patient care and the well being of healthcare providers.

Gavin de Becker, author of The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence, put it this way, “Only human beings can look directly at something, have all the information they need to make an accurate prediction, perhaps even momentarily make the accurate prediction, and then say that it isn’t so.” He was referring to a unique feature of the human psyche that causes us to ignore our own instincts. They are the very same instincts that cause a deer to run when it sees a bear in the woods. But when a human being sees a bear, while driving through some National Park, he sometimes gets out of his car and takes a picture. Even though people receive the same danger signals and feel the same fear as a deer, they often disregard them. Sometimes we get the picture we want and other times we get mauled to death. We are the only animals on earth to take such risks for such little return.

That is a great irony considering that we occupy the top of the food chain. Didn’t we get to the top partly because of our big brains? Perhaps the ability to rationalize away our fear is why we ride motorcycles, skydive, cross oceans in wooden boats, build skyscrapers, and fly to the moon. On some level, our fearlessness has broadened our experience, enriched our lives, and carried us to horizons other species aren’t even capable of imagining. But it is also the same fearlessness that carries us off to war, generation after generation. It is also partly to blame for why, day in and day out, we continually create professional relationships and foster environments of care that are compatible with violence. The purpose of this book is to proclaim that it doesn’t have to be that way.

The paradigm of acceptance for violence in healthcare must be abandoned. We must create environments of care and professional relationships that are incompatible with violence and more compatible with patient compliance, cooperation and collaboration.

In any environment, even in a church or a toy store, violence may occur. Still, everyone intuitively understands that some environments are more compatible with violence than others. That notion simply acknowledges that fights are more likely to break out at the corner tavern than your local library — we all get that. Ultimately, the amount of violence that occurs in any setting depends on its established Social Contract.

Proper policies, procedures, and training can establish and maintain a Social Contract that excludes violence, generates patient collaboration, supports more peaceful and attractive environments of care, and results in better patient outcomes. It all starts with healthcare professionals believing and expecting that violence is unacceptable. Only when healthcare providers embrace a new belief system about violence, can they begin to form safer and more therapeutic relationships with their patients.

Once we’ve convinced healthcare professionals to stop accepting violence as the norm, we will have to expand their definition of violence. In 2007, Dr. Lauretta Luck, the principle investigator who conducted the seminal STAMP study at the University of Western Australia, published her findings in the “Journal of Advanced Nursing,” entitled, STAMP: components of observable behavior that indicate potential for patient violence in emergency departments. Dr. Luck and her colleagues discovered definite signs in patient and family behavior that reliably signal the potential for violent assaults. Her team organized these behaviors into five categories: staring and eye contact, tone and volume of voice, anxiety, mumbling and pacing.

In most cases, like when sitting on a subway train for instance, we quickly and accurately identify the threatening individuals that might cause us to get up and walk to another seat or get off at the next stop. They are the ones who are staring at us or perhaps looking around in an odd manner. Or perhaps they are talking loudly to another person in an angry tone. They might be rocking back and forth anxiously in their seat. They might be talking to themselves or pacing up and down the aisle. All the above behaviors are familiar signals that this is a person under stress or in crisis. All of them are STAMP behaviors. The trouble seems to be that we take action or don’t take action, depending solely on the context.

Missed Signals

One of the things medical workers often say after a violent assault is, “it happened out of the blue!” That is almost never the case. In most cases, attackers signal their victims several times that an attack is possible, well before it happens. This phenomenon is no doubt a function of denial, but the problem may be even worse in healthcare, due to the erosion of our perception of personal space. The concept of Proxemics 10-5-2, developed by Dave Young, a Director at Vistelar, are discussed later. These skills are designed to compensate for our lack of healthy fear, as healthcare professionals, and protect us from our own very human impulses to rush in, get to close, and say too much when people are angry and distressed.

STAMP behaviors are no doubt increased in an environment filled with sick, injured, and worried people. That said, it is all the more reason to re-sensitize providers to recognize the Gateway Behaviors of Violence and train them how to respond when STAMP behaviors are observed. By teaching providers how to respond correctly to behaviors, we can keep them safer.

STAMP behaviors are a kind of gateway behavior. But gateway behaviors can also be very deliberate. When someone begins to curse, for instance, in an environment where it would commonly be viewed as inappropriate, they are often trying to elicit a response from bystanders. When persons curse in front of children and families in our hospitals and clinics and we say nothing, the non- verbal messages of our silence are “it’s acceptable”, “I’m afraid”, “I have no authority” or “I don’t care.”

When people curse and otherwise behave inappropriately, they are sending out, what are in a sense, verbal “radar waves” to see what signals bounce back. When the answer they receive is silence, they begin to gain power and authority over the group. Once they become comfortable with making others uncomfortable, they begin to turn up the heat. Often this takes the form of yelling or shouting. When we remain silent they also become comfortable shouting at us. Then they begin to threaten us, often in the form of an implied or veiled threat. Examples are, “Touch my kid again and see what happens” or “Send that doctor in here again and she’ll be sorry.”

The Importance of Addressing Gateway Behaviors

Once people become comfortable implying they will hurt us, then they often just blatantly threaten us, by saying things like “Stick me one more time and I’ll knock you out!” In healthcare, perhaps more than in any other profession, customers routinely threaten staff with absolute impunity. So, when people get comfortable threatening us and they can do so with impunity, why not hit us? That is the question we often place in the minds of our attackers, when we fail to train to manage aggression and set limits on bad behavior. All cycles of interpersonal violence develop this way, whether it’s one between nations or individuals. Whether it’s a schoolyard fight or a domestic violence relationship, it all begins the same way and usually ends up badly for the victim.

When gateway behaviors are observed in patients and visitors, trained healthcare providers can reliably minimize their anxiety, assuage their fear, set limits on inappropriate behaviors, and address their underlying issues, thereby diffusing the potential for violence. That formula leads to safer and better medicine. People get better medicine because, if people feel safe in our hospitals and clinics, they might not avoid them. Also, if healthcare providers don’t fear their patients or their visitors, they might spend more time with them and make fewer mistakes.

If we intervene early in the gateway behavior cycle, we can stop the journey towards violence. If we can stop people from cursing and yelling, they may not graduate to threatening and violent behavior. Ultimately, it is much easier to stop someone from yelling than it is to stop them from hitting. But we can’t even begin, if we don’t understand how or when.

Even in the most peaceful environment, anyone can find themselves in a threatening or violent situation. No violence prevention and management system would be complete, unless we trained providers and staff what to do to diffuse violence, should it rear its ugly head. Everyone understands that before we can learn to run, we must first learn to walk. So doesn’t it stand to reason that before we learn to de-escalate, we should learn to non-escalate? The concept of non-escalation is a cornerstone of what we do as healthcare violence consultants and trainers at Vistelar and is part and parcel of creating environments of care that are incompatible with violence.

If you still doubt that focusing on unwanted behaviors can lead to systemic change, you might consider this. When I began my career in healthcare in 1991, smoking was allowed in hospitals. Scarcely a decade ago smoking was pushed completely outside of American hospitals, as their ever-shrinking “smoking lounges” were closed down and smokers were banished to the sidewalk. Now smoking isn’t even allowed on most hospital campuses.

Restaurants no longer allow smoking, despite all the unfounded fears of restaurant owners that their businesses would close down. Then soon followed the bars and taverns; the last vestige of public smoking, the places where nobody thought smoking would ever fade away. Now you can’t rent a hotel room or even an apartment that allows smoking by its tenants. In a few short years we, as a society, decided to address smoking; and, as a result we have all but driven smoking entirely from the public experience. Something many speculated could never be done.