Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 6

Taking Action

The Art of Bystander Mobilization

The TAKES ACTION acronym, (which I co-developed) was created in response to the need for a comprehensive bystander intervention program rooted in applying “how to intervene” above and beyond just understanding why we need to intervene. The acronym is based on more than 40 years of social science research and is easily operationalized in any environment, for any situation.

The TAKES Acronym

The first part of this model is TAKES. It stands for “Threat Assessment Keeps Everyone Safer.”

TAKES focuses on the importance of safely assessing situations to support a safe community.

The key to this all is being personally aware of your environment. Your ability to recognize situations requiring disruption will depend greatly on how ambiguous the signs are (red flags and anomalies) but will also hinge on how aware you are in that moment and in your environment (also refer to when/then thinking and conditions of awareness in Chapters 4 and 5).

For example, if you saw someone with a major injury, there would be no doubt in your mind that you would call for help. However, intervention is still needed in situations such as a coworker’s absenteeism, depressed mood, or increased drinking behaviors, but it is harder to recognize.

It is important that when we recognize these signs, we take the time and effort to communicate with each other. It is much more important to identify and ask the difficult questions rather than ignoring the problem “hoping it will take care of itself.” It will not.

Note that the company at which I work, Vistelar, teaches several tactics in its Non-Escalation, De-Escalation, and Crisis Management training program that specifically apply to the TAKES model. These tactics include Be Alert & Decisive, Respond - Don’t React, and Proxemics 10-5-2.

The ACTION Acronym

The second part of the TAKES ACTION model is the ACTION acronym. It was developed to operationalize the ethical decision- making steps necessary to safely intervene.

Aware: Notice the event and interpret it as a problem. Identify red flags and assume personal responsibility to help.

Create: Create possible solutions. Think it through and pick the most effective strategy.

Take your time and tag team: Stay calm and slow things down. Enlist help if you can.

Intervene: Intervene when it is safe and appropriate. Timing is an undervalued element of communication.

Open dialogue, observe, and offer options: Be conscious of and deliberate with your delivery style. Use perspective-taking, set the context, and communicate in light of the desired outcome goal.

Negotiate a solution and negate further conflict: Draw a mental line in the sand and know the appropriate next step.

As discussed previously, determining what actions are appropriate will depend on your training, experience, and employment role. Your prescribed duties, intervention capability, organizational policies, and local laws will guide you.

Determining appropriate action will also include a cost/benefit analysis of:

- Personal biases (also consider: the ladder of inference).

- Identifying or developing alternative courses of action.

- Analyzing both short-term and long-term risks.

- Taking action with a commitment to accept responsibility for the outcome.

- Evaluating if the actions are likely to prevent future occurences.

Threat Assessment and Environmental Risk Assessment

A lack of basic assessment skills is another issue that combines to create a laterally violent and violent culture in the workplace. We are generally poor at recognizing the cycle of violence. When we drive a car, we look ahead, to the sides, and occasionally behind us. We listen, we interpret traffic patterns, we look for danger, and we plan how to extract ourselves from danger. We also think about what measures we might take should danger spontaneously present itself. We should be conducting the same types of assessments in our work environments. At its most basic level, a risk assessment can be understood as a systematic process of evaluating what risks you are vulnerable to. You need to be able to identify your vulnerabilities accurately so you know what risks you might face, and you need to be aware of the elements in your environment that pose threats to those vulnerabilities. To make it simpler to understand, consider it a hazard assessment of an area.

Threat assessment is the practice of determining the credibility and seriousness of a potential threat (whether something is an actual, inherent, or potential threat) and the probability that the threat will become a reality (determining the intent and capability of the threat actor). Consider it a hazard assessment of a person.

Threat assessment aims to interrupt people on a pathway to committing laterally violent or violent behavior. It is an objective, fact- finding process designed to identify, assess, and manage the risk of violence that a particular person poses.

In a given situation or of a specific person, threat assessment is a continuous process. It is not something you do “just one time.”

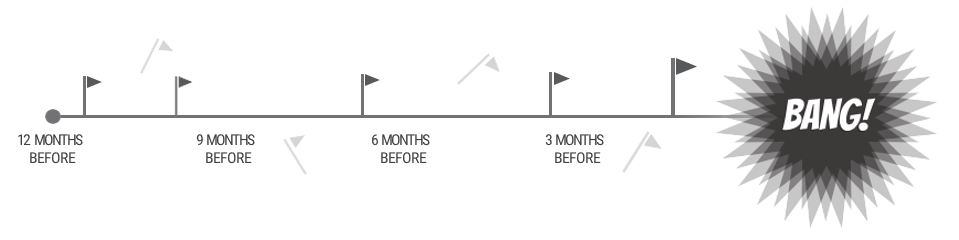

The better we are at identifying pre-incident indicators or precipitating events (red flags), the better we will prevent or avoid potentially dangerous situations. These red flags are often identified after the fact, causing us to say things like, “Oh, wow, I should have seen that coming—all of the signs were there!” The goal is to identify these behaviors on a timeline—before, or “left” of, the event.

Over time, we become desensitized to toxic tactics and laterally violent behaviors because of our constant exposure to them. We start disregarding pre-incident indicators and become complacent with who we allow into our personal space. Many workplaces have formed a culture of denial that dismisses threatening behavior and fails to understand the negative impact of antisocial and uncooperative behavior.

The Be Alert & Decisive tactic (taught in the Vistelar Non-Escalation, De-Escalation, and Crisis Management training program), serves as the foundation for personal safety and overall readiness.

Be Alert is understood as what to look for. Become proficient in behavioral observation, situational awareness, and decision-making.

As Vistelar teaches, when you enter your area of observation, quickly perform a scan for any immediate threats, and get a feel for the atmosphere. In this case, listen for and look for anything that could cause emotional or physical harm to you or anyone else. Assess the body language and demeanor of those in the room. Be on the lookout for aggressive posturing, any weapons or potential weapons, or anyone paying more attention to someone else (or you) than to what they are doing. Start close and finish far. This is important because the closer a potential threat is, the less reaction time you have. Threats that are closer to you are usually a higher priority.

Then you must evaluate the totality of the circumstances.

We have to observe behaviors (individually) and then communicate and collaborate (with others) to share what we know. This will help you, as a team, in identifying clusters of behavior that warrant additional attention and potential action. This is why organizations have multidisciplinary and multi-agency threat assessment teams that share information freely. Generally speaking, no one person has seen all of the indicators, and working together will allow you to stay “left of bang.”

Dispelling the Myth Case Study: “He just snapped!”

Tony worked for a large construction company driving heavy equipment. He had been working there for almost 30 years and was nearing retirement.

He was an exemplary employee. He always came to work early, stayed late, and produced the highest quality work. He had a great attitude, loved to laugh, and other employees enjoyed being around him. They all knew that if Tony were assigned to their team, their project would finish on time and on budget.

It didn’t seem to matter how much extra work the foreman gave him; Tony would just get it done. He never complained. He never failed. He’d just make it happen.

Tony was well respected by his peers because, despite pressures to finish jobs on time, he always did them “by the book.” He followed all the safety procedures because he knew it could be a matter of life or limb on job sites like his.

One day Tony and his team were assigned a very large project—a new factory built near the outskirts of town. Several very large pieces of specialized equipment were brought in, including a massive Transi- lift heavy crawler crane.

The operation of the crane came with many safety precautions, including things people don’t often think about, such as requiring an experienced operator to operate, needing near-perfect weather conditions, and ensuring all major motorized components were inspected and signed off on at multiple points throughout the day.

Tony was the primary crane operator for the first several weeks on the job site and followed these precautions “to a T.”

Unfortunately, the project started falling behind, and Tony’s corporate office ordered additional help to assist with the build around the clock. Far less experienced employees were now on the job site, and Tony was very protective of them. He explained to the foreman that no one should operate the crane without a minimum of three years’ experience as a crane operator.

But the foreman didn’t listen and had someone far less experienced, Charles, start operating the crane when Tony wasn’t there. Upset, Tony again expressed this as dangerous to his foreman. The foreman didn’t change his decision. In fact, the foreman was more concerned about hitting the project deadline, so he started letting other safety precautions go, such as helmets, safety glasses, and the use of seat belts while operating company equipment. He felt those precautions were just slowing them down. Tony was upset but carried on. Charles called in sick one day, and the foreman asked Tony if he would come in on his day off. Tony told him no.

A few more weeks went by, and the employees on the site started to notice the quality of work going down. They realized that Charles wasn’t experienced enough to complete the build, and it had become obvious that finishing the build on time was more important than building it well. While they were concerned, they weren’t concerned enough to “bother” or “risk upsetting” the foreman.

Seeing this, Tony had had enough. He talked to the foreman one more time, who blew him off. Tony then reached out to the corporate office and cited numerous safety violations occurring on a daily basis and stated that “he couldn’t bear to see any one of his team members hurt.” Corporate was silent. They wouldn’t return his calls (which were now daily), and they wouldn’t respond to his emails (which were now weekly).

Tony was furious. He was furious and frustrated but internally torn. He was so close to retirement … did he really want to ruffle all these feathers now?

A few days later, Charles had an accident while operating the crane in high winds. Multiple workers were injured, including Tony’s best friend, who was injured the worst. Tony’s friend was paralyzed from the waist down and unlikely ever to walk again.

A short while after the incident, numerous interested parties became involved in the investigation to determine what happened. Members of the corporate office made a statement that the incident was a “fluke,” that “all safety precautions were followed as per statute,” and that they had no wrongdoing in the matter.

Tony couldn’t take it anymore.

Hearing this on the news and knowing it was a complete lie, he couldn’t bear it. He felt personally responsible for the accident and for paralyzing his best friend. So he went to his office and started typing an email to the investigators. And he kept typing, and typing, and typing. The more he typed, the angrier he got. And finally, he got so angry that within seconds of hitting the “send” button, he picked up his entire computer and threw it out of a second-floor window. The computer crashed to the ground, and luckily, no one else was hurt.

Tony was fired the very next day.

When human resources asked his foreman about his behavior, he responded, “I don’t know. I don’t know what happened. He … he just snapped.”

If you break this story down, piece by piece, you can easily determine the situational and environmental baselines and the anomalies. Looking at how it ended and working backward on the timeline, you should be able to identify numerous interjection points that would have kept this situation “left of bang” and likely saved Tony’s career.

Proxemic Management

A key component of managing your personal safety involves not only evaluating and assessing your surroundings but also managing your space. We can manage distance by practicing proxemic management or the reduction of risk through proxemic shifts—adjustments made to increase safety in your physical space.

Proxemic management is a concept I developed to describe the skill of actively managing distance and space. Time and space are viewed as both an opportunity and a tactic.

Proxemic management enables you to take ownership of your space and empowers you to stay emotionally and physically safer within that space. It encourages you to be mindful, not fearful, of environmental conditions that could increase your chances of being victimized (regardless of the offense: harassment, theft, assault, etc.). To stay safe, the space you need to control isn’t just directly in front of you. It includes the evaluation of your complete 720-degree bubble to get a full picture of everything that is going on around you. It includes looking in front of and behind, left and right, and at everything above and below you. This includes assessing all the potential environmental factors that could enter and/or change that space.

Proxemic management also includes considering your position in relation to other people (also known as relative positioning) and assessing barrier options or exit strategies. Barrier options are things like tables, chairs, corners, pillars, escalators, and garbage cans: basically, anything that you can use to create a barrier, either permanent or temporary, between you and the other person (or potential threat) that will help you create time and distance from them, if you need to. Also, consider the air temperature, the conditions of the walking surface, perhaps a low ceiling or a low hanging shelf, the number of people walking by, or how crowded it is. This also includes things like walls, doors, desks, and chairs and could include cars driving past, how fast they are driving, and if there is a stop sign nearby.

When it comes to understanding proxemics and space management, you have to get creative and really think about all the factors in that space that change your level of safety in it.

Here’s a quick example:

If you were to go to your human resources office on any given day, most reasonable people would agree that it would be pretty safe to go there in comparison to going there on a day when multiple people were about to get fired or laid off. By going there on any “normal” day, you wouldn’t run the risk of engaging with people having heightened emotions (particularly that of fear, anger, and rage) and therefore, having quite varied, unpredictable, and potentially volatile reactions.

So in this example, you could still choose to go to HR on the day of mass layoffs, but in evaluating the proxemics and the totality of the situation, the choice to do so is clearly less desirable and less safe than the other.

However, in the event you unknowingly walked into HR during a termination whereas the (now former) employee lashes out by screaming, crowding, shaking their fists at people, and issuing direct threats, you’d now have a tool you could use to manage your safety in the moment. The simplest, safest, and most effective answer would be to manage your proxemics by leaving the area.

If you’re unable to leave, work to maximize the distance between you and the aggressor. If you’re unable to maximize your distance, work to put a barrier (or barriers) between you and them - a desk, a cubicle, a pillar, or a wall. The barrier will not only help you create distance, but will also help conceal you from their view. If you’re unseen, you’re less likely to become the target of their anger, regardless if it manifests as a verbal onslaught or physical assault.

In the field of communication, proxemics refers to the study of non- verbal communication and how distance affects how we communicate with each other. It is the study of the cultural use of space. For the purpose of managing conflict, proxemics refers to where you are positioned in relationship to another person and how it impacts your ability to safely communicate, both verbally and non-verbally.

We encourage you to take ownership of your space and be empowered to stay emotionally and physically safer within that space. We encourage you to be mindful, not fearful, of environmental conditions that could increase your chances of being victimized.

Managing proxemics is about using position as leverage. Time and space are seen as an opportunity and a tactic: you choose what you do, when and where you can most safely do it.

Space equals time, and time equals options.

There is a subjective time-distance relationship (known as the reactionary gap) that can be used to determine reaction time based on distance. There’s also an injury-distance relationship (known as the liability gap). There is a direct correlation between injury potential and the distance from a threat.

The distance needed to stay safe from a threat can be measured by assessing the potential personal damage based on the available weapon system (hands/feet, pens, knives, clubs, firearms, vehicles etc.), the specific target (someone or someplace), and the scale of injury or damage.

Ultimately, understanding this space-distance safety relationship is pivotal to understanding de-escalation as it relates to space:

- Create distance: Engage in proxemic management.

- Buy time: Slow things down and create more space.

- Persuasion communication: Defuse literally, or diffuse the energy in the space using your communication skills.

The concept of proxemic management is incorporated into a tactic taught in the Vistelar Non-Escalation, De-Escalation, and Crisis Management training program named further Proxemics 10 - 5 - 2. This tactic operationalizes what you should be looking for and what you can do when 10, 5, and 2 feet away from someone.

No matter how you look at it or how you choose to define it, there is no denying the relationship between your safety and the distance you maintain from a potential threat.

Intervention Strategies

Throughout this book, we have made it clear that it is everyone’s responsibility to do something when an inappropriate or unsafe situation occurs. However, the intervention strategy you choose to employ will be dependent on a number of factors. You must evaluate the totality of the circumstances and then assess the options available to you based on your training, experience, and comfort level. If you choose to intervene, choose the safest and most effective strategy that will maximize your strengths.

The strategies below were developed by multiple universities, including the University of Arizona, Virginia Tech, Syracuse, and Marquette University, and are compiled here to assist you in understanding all of the intervention options and creative strategies available to you that can apply across a variety of situations.

Presence

Sometimes your presence alone is enough to deter a situation. Think about surveillance cameras in a room; people will generally alter their behavior because they know they’re being watched and could get caught. If you are known as a person who won’t tolerate lateral violence, the likelihood of it occurring in your presence will decrease.

Presence as a strategy is also useful because it allows you to monitor a situation from a safe distance. This way, if you’re unsure if a situation requires help, you can observe it and take mental notes of what is going on in case something does go wrong.

Here are a few additional elements of using presence as a strategy, originally developed by Vistelar co-founder Dave Young:

Acknowledge presence: The actor may not know you are there.

Confirm presence: You see the actor make eye contact or alter their behavior after seeing you.

Contact presence: You engage with the actor.

Verbal: You engage in conversation with the actor.

Barrier: You find or create a barrier between you and the actor.

Monitor: You monitor the situation from a safe distance.

Group Intervention

There is safety and power in numbers. The group intervention strategy is best used with someone who has a clear pattern of inappropriate behavior where many examples can be presented as evidence of their problem or unprofessionalism. This strategy is designed to let others know that they are not alone in their discomfort. For example, if a coworker makes several racist jokes, you might simply turn to the group and ask, “Am I the only one uncomfortable with this?” This creates options by allowing you to evaluate the situation and recruit the help of colleagues to determine the best course of action.

Clarification

People who verbally express negative attitudes towards others expect other people to go along with them, laugh, and join in. They do not expect to be questioned. By asking a question like, “I’m not really sure what you meant by that. Could you please explain that to me?” you create the opportunity for them to rethink the assumptions that underlie their statements and attitudes and also empower others to express their disagreement in a way that is not disrespectful.

Disagreement is okay; disrespect is not. Just because someone’s opinion differs from yours doesn’t automatically make them wrong. Two people can look at exactly the same thing and see something totally different. And that is okay.

Bring It Home

The “bring it home” strategy is designed to create perspective for whoever is acting in a degrading manner. It “re-humanizes” their target and makes them think about what it would be like if someone treated somebody they knew like that. For example, if someone makes fun of another employee, saying they’re “completely incompetent” because they have Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), you could simply say, “Whoa, time out. How would you feel if your brother had ADD and someone talked about him like that?”

“I” Statements

Think about how you feel when someone points the finger at you and says in an accusatory voice, “You really need to stop acting like that; you’re embarrassing the family.” Instead, “I” statements are easier to hear since they are about the feelings and thoughts of the person making the statement and not criticizing and accusing the other person. People are less likely to become defensive when using “I” statements. For example, you could say, “I find it embarrassing when you act like that. I’d like it if you could change your behavior in the future.”

Humor

Humor is a difficult strategy as it can easily escalate if people feel they’re being mocked. However, using humor effectively can reduce the tension inherent in the intervention and make it easier for the person to hear you. Be careful, though, not to be so funny that you undermine the point you’re trying to make. In my experience, humor is best used as a strategy if you have a close or positive working relationship with someone. For example, if you overhear a coworker make a harsh or discriminatory comment about the perceived ability or competency of a new hire, and you could choose to address the comment by saying, “Woah, now hey. You were new here once too and you turned out… ok.” If you delivered that engagement phrase with a positive and playful tone, and a wink or a smirk, that comment would likely get the point across in a non-escalatory way.

The Silent Stare

The “silent stare” or “the look” works very well if you connect it to parents, who have the ability to communicate their displeasure with their child’s actions simply by staring or giving you “a look.” No words even need to be spoken. Sometimes a disapproving look can be far more powerful than words. Think about a time when someone you really respected just looked at you and shook their head in disapproval. Remember how awful you felt? I sure do.

Distraction

The goal of distraction is not to directly confront the situation but rather to interrupt it and change its course. This is an especially useful technique where there is a higher risk of heightened emotions, like a heated work argument over a missed priority deadline. In this situation, you may have multiple people engaging and only one of you. Use a distraction, such as by saying, “Hey, I think lunch is finally delivered,” or “I’m pretty sure the boss just walked in,” to redirect the focus somewhere else or draw attention away from the argument.

“We’re Friends, Right?” or “We’ve Worked Together a Long Time, Right?”

This strategy works best if you can take your colleague off to the side or if you can wait until later to address them. That way, you can avoid humiliating them in front of their peers and increase their likelihood of hearing and valuing what you say. For example, if you overhear a coworker saying something awful or untrue about another coworker, you can talk to them after the fact and say, “Hey, we’ve worked together for a long time, right? I don’t want to fight with you, but what you said about Tom earlier is actually untrue. I was there.”

Cut and Divide

The “cut and divide” strategy relies on creating space and physical separation between the involved parties. Recruit help if you can, as it is much easier to separate and support multiple people when you have additional people. Use sound proxemic management and communication skills to separate them. By separating them and getting them out of the eye sight or ear shot of the other person, you can help them cool off and prevent them from trying to posture or escalate in front of their friends. By having no “audience,” they will potentially have less motivation to show off or escalate. Don’t use this strategy where your threat assessment results in the potential risk of physical injury.

Take a Picture

The “take a picture” strategy encourages you to use your technology to your advantage. People immediately sensor their behavior when they know they are being recorded. Pretty much everyone has a camera phone, so it is now easier than ever to record good witness information. Notice a security camera? Politely point it out to the person acting up, and remind them that it’s not worth getting caught.

Key Takeaways

- The TAKES ACTION acronym helps bystanders understand how and why to intervene.

- TAKES: Threat Assessment Keeps Everyone Safer.

- ACTION: Aware, Create, Take Your Time/Tag Team, Intervene, Open Dialogue/Observe and Offer Options, Negotiate a Solution and Negate Further Conflict.

- Threat assessment is the practice of determining the credibility and seriousness of a potential threat and the probability that the threat will become a reality. It aims to interrupt people on a pathway to committing laterally violent or other unsafe behavior.

- Proxemic management enables you to take ownership of your space and empowers you to stay emotionally and physically safer within that space. Time and space are both an opportunity and a tactic: you choose what you do, when, and where you can most safely do it.

- There are many intervention strategies. Evaluate the totality of the circumstances, assess the options available to you, and use the safest strategy that maximizes your strengths.