If you work in healthcare spending long days with inpatients, then you probably know all too well about eye-rolling. Should we do something about it? What can we do about it? And what about all the other nonverbal slights and insults some patients hurl our way, while we’re just trying to provide them with the best and safest care? First, we should remind ourselves that most of our patients treat us with respect. Only a few of them treat us disrespectfully. That said, what harm do the few patients who treat us with disrespect do, and what are those patients trying to tell us?

Handling Passive-Aggressive Behavior

Passive-aggressive behavior from patients, coworkers, visitors, and anyone else in our professional and personal sphere of contacts can wear on us. It can make us doubt ourselves and resent our patients and coworkers. It can affect our moods, emotional health, job satisfaction, and even patient outcomes. That’s right—patient outcomes. Because whether we like to admit it or not, the more we dislike a patient, the less time we might spend with them. Also, if we fail to address passive-aggressive behaviors, we are almost assured a poor patient experience survey and will lose the opportunity to change their minds about us, our hospital, and their quality of care.

personal sphere of contacts can wear on us. It can make us doubt ourselves and resent our patients and coworkers. It can affect our moods, emotional health, job satisfaction, and even patient outcomes. That’s right—patient outcomes. Because whether we like to admit it or not, the more we dislike a patient, the less time we might spend with them. Also, if we fail to address passive-aggressive behaviors, we are almost assured a poor patient experience survey and will lose the opportunity to change their minds about us, our hospital, and their quality of care.

Vistelar’s proprietary term of non-escalation is gaining notoriety in healthcare. Although the terms sound similar, the distinction between de-escalation and non-escalation is important and should be understood by all contact professionals. Perhaps the following example will be useful in understanding that difference: De-escalation is what you say and do to get someone down from a ledge instead of jumping from it. Non-escalation is what you say and do to keep someone from climbing up on that ledge in the first place.

Healthcare providers and other contact professionals often miss the clues that conflict is building. Even if they realize it may be coming, even fewer of them know what to do to prevent the conflict in the first place. De-escalating a conflict is much harder and more dangerous than non-escalating it to begin with. Therefore, shouldn’t all healthcare providers learn this important skill set? First, learning begins with a complete understanding of a concept. Just like any gateway behavior, conflict and crisis situations both have a beginning a middle, and an end. The beginning can be very subtle, even something as subtle as eyerolling.

Once, while consulting with a nursing administrative group, I was asked to analyze the results of a nursing satisfaction survey. As is often the case, the overall feedback was very poor. The nurses were satisfied with their pay and with their benefits. They liked the facility they worked in, and many liked their leadership. Yet, they rated their overall job satisfaction as low and many said they were looking for other employment opportunities.

The hospital administration was perplexed, but in my experience, this result was commonplace among nursing staff. Further, I also recognized a recurring theme in these surveys. The nurses didn’t like the way they were treated, and they hated patient satisfaction surveys. To paraphrase several common written responses, “We’re so worried about patient satisfaction surveys that we let them [patients and visitors] walk all over us.”

In the written portion of the survey, there were several references to patients yelling and otherwise disrespecting them. As we reviewed responses out loud in our group, eye-rolling was mentioned several times. As one team member read aloud another complaint about eye-rolling, another member exclaimed, “What do they want? We can’t stop people from rolling their eyes!”

To that I responded, “Yes you can, and you should.” After the collective look of shock subsided, I explained why it’s important to address eyerolling and how to do it.

Addressing Gateway Behaviors (including Eyerolling)

Eyerolling is a gateway behavior that signals something is wrong in the moment. It means that something you just did or said was inappropriate, annoying or irritating to the sender (the eye-roller). If you don’t address the behavior, the meaning to the sender is limited. Usually it is interpreted as you don’t care that they rolled their eyes, and therefore, you don’t care about their issue. Or, that you’d rather avoid a possible confrontation than address it. In either case, we are likely to earn the patient’s resentment or disrespect.

Disrespectful language—including nonverbal language—and how to address it is one of the places where we usually stumble. Disrespect is often the beginning stage of conflict in a professional encounter. One form of disrespect is eye-rolling. When it occurs, many nurses ignore it and just go about their tasks, while others will try to try to gain their patient’s favor by “killing them with kindness.” However, neither of these strategies really work. In fact, they may encourage more and escalating disrespect because they can make the nurses appear weak and submissive.

However, by using a simple and safe method of non-escalation you can nip the cycle of conflict in the bud. This is an example of a redirection, another skill trained by Vistelar’s instructors.

Nurse: “Ok, Ms. Johnson, your vital signs are very good today. I read in your chart that the test results from yesterday were good too. That’s very encouraging.”

Patient: [remains silent and rolls eyes]

Nurse: “Are you not feeling well, Ms. Johnson, or is something bothering you about your treatment. Please tell me what it is, so I can correct it.”

During the above encounter, the nurse acknowledged that the patient was dissatisfied with something without being confrontational. In other words, she didn’t say “Why did you roll your eyes at me?” By acknowledging and redirecting, the nurse gives the patient the opportunity to discuss the issues that are bothering them.

being confrontational. In other words, she didn’t say “Why did you roll your eyes at me?” By acknowledging and redirecting, the nurse gives the patient the opportunity to discuss the issues that are bothering them.

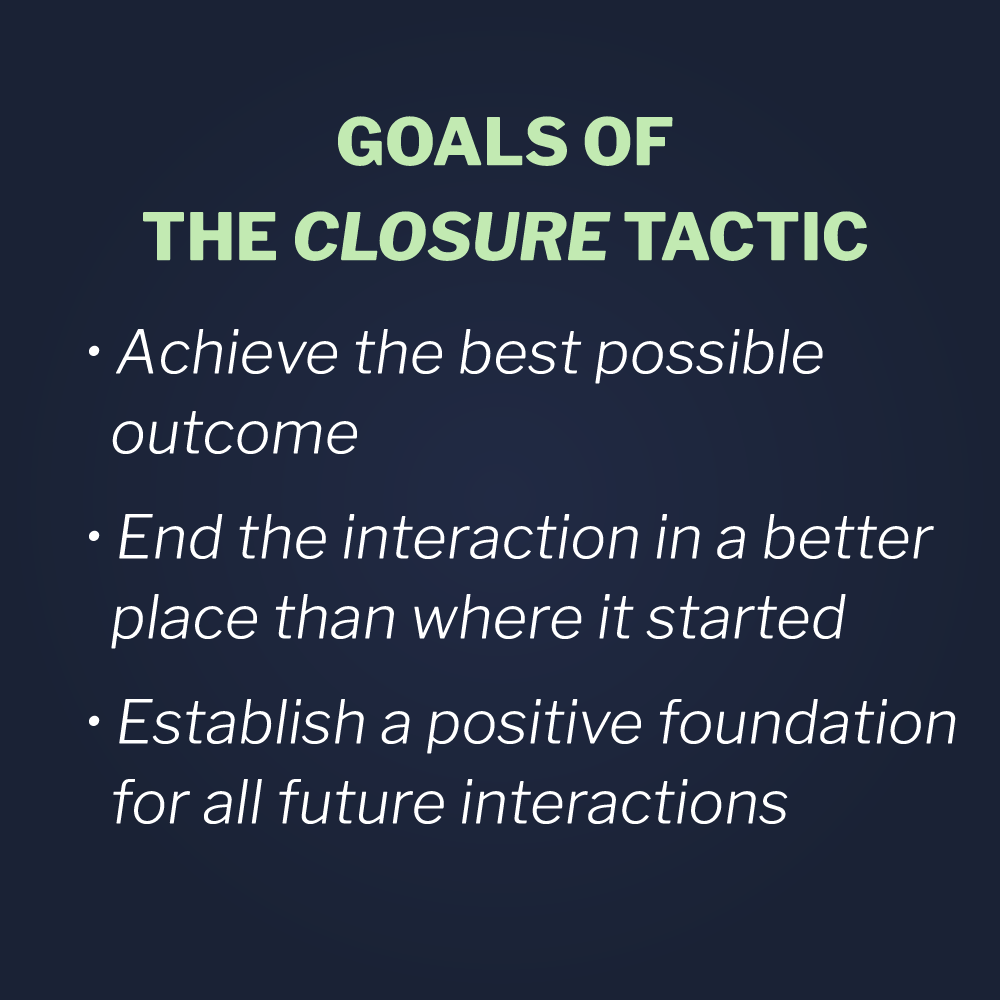

In most cases, the final phase of the conflict cycle is the recovery phase or closure. This is when the nurse takes the opportunity to address the patient’s concerns and discover their expectations. The nurse then can take appropriate action and establish a social contract for moving forward. In the case of eye-rolling, closure should sound something like this, “I’m glad we talked, Ms. Johnson. I didn’t know that you didn’t understand the doctor’s instructions for you. If you have any more questions, please talk to me. I don’t want you to have to worry needlessly. I’m here to make this time as easy as possible for you.”

To learn about who we train, click here.